1.

Introduction

The young Achuar indigenous people of Ecuador face multiple challenges in expressing their emotions and sharing their cultural heritage in Spanish, as it is not their native language. Achuar, a native language deeply rooted in their worldview and spirituality, features symbolic and narrative structures that are challenging to translate accurately into Spanish. This linguistic barrier limits not only emotional communication, but also cultural transmission in educational or social spaces dominated by the official language. Additionally, there is limited external validation of their cultural practices, which creates tension between pride in their identity and pressure to conform to Western models.

Added to this is the lack of access to professional and creative tools (narrative writing, cultural documentation techniques through art) that would allow these young people to tell their stories, rituals, and traditions from their own perspective. The absence of training processes tailored to their cultural contexts threatens to accelerate the loss of ancestral knowledge. Without strategies that integrate the Achuar language and intercultural approaches, there is a risk that voices that are fundamental to Ecuador’s living heritage will be silenced. It is urgent to work together with these communities to strengthen their own ways of telling and preserving their world.

On the other hand, storytelling, as a narrative writing technique and tool for cultural expression, has proven to be an effective means of facilitating communication, particularly in contexts where individuals face emotional or social barriers that hinder them from opening up. In this context, this study aimed to determine whether storytelling can serve as a valid tool for Achuar youth to express their emotions more freely and affirm their cultural identity through narratives accompanied by artistic drawings.

1.1 The Achuar culture in Ecuador

The Achuar culture, primarily settled in the provinces of Morona Santiago and Pastaza in the Ecuadorian Amazon, represents one of the most emblematic Indigenous nationalities of the country. This culture is characterized by its profound respect for nature, its spiritual worldview deeply rooted in the forest, and its social organization centered on community autonomy (Medina, 2002). The Achuar language, part of the Jíbaro linguistic complex, is a vital tool for transmitting knowledge, myths, and ancestral wisdom (Deshoullière & Utitiaj, 2019; Mejeant, 2001). Their life revolves around the chagra, where they cultivate products such as cassava and plantain—a practice that also holds ritual and educational significance (Giovannini, 2015; Ríos & Carrascosa, 2017). Despite increasing pressure from Western educational and extractivist models, the Achuar have steadfastly defended their cultural identity, resisting through bilingual education and community-based ecotourism as alternatives for autonomous development (Carpentier, 2014; Tym, 2022).

1 The chagra is a traditional agroforestry system used by many Indigenous groups in the Amazon, including the Achuar. It is more than just a cultivated plot of land — it is a central element of subsistence, culture, and education. It is also a sacred space. It reflects their relationship with nature, cosmology, and the spirits of the forest.

1.2 Gender differences in indigenous communities

In the indigenous communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon, gender differences are expressed not only in terms of the division of labor but also at the symbolic, spiritual, and organizational levels. In many nationalities, such as the Kichwa and Shuar, women have played significant roles in the productive and ritual spheres, but have historically been excluded from formal political spaces. However, among the Achuar, gender relations have been characterized by a more marked complementarity, where women exercise authority in the domestic, agricultural, and ritual spheres, while men predominate in warrior and communal leadership spaces (Descola, 1996; García, 2004).

Recent studies reveal that, although traditional roles are being reproduced, paths are also opening up for female participation in indigenous organizations and debates on territory, health, and extractivism (Delgado & Ochoa, 2022; Vallejo, 2017). These transformations vary across nationalities, and in the case of the Achuar, tensions are particularly evident between traditional gender practices and dynamics imposed by external actors, such as the state and oil companies (Portocarrero, 2018). In terms of gender behavior, it has been found that in Amazonian indigenous communities such as the Achuar, women tend to be more reserved or shy in public spaces. In contrast, men tend to assume more visible and leadership roles. This difference is not merely individual, but responds to cultural norms internalized since childhood, where female expression is associated with respect and modesty, and male expression with authority and negotiation. Bonilla (2002) explains that these forms of socialization reinforce stereotypes of female submission, but also notes that many indigenous women have begun to challenge these expectations, particularly in contexts of political mobilization and territorial defense. Thus, female shyness, far from being a biological or essentialist constant, should be understood as part of a cultural construct that is increasingly being questioned from within the communities themselves.

1.3 Storytelling as an effective technique for cultural expression

For several years now, storytelling has been proven to play a crucial role in the cultural and emotional expression of indigenous peoples in Latin America. Gumucio (2002) has highlighted the importance of cultural expression in the struggle for the recognition of indigenous rights and ancestral lands. This is also supported by Riascos (2007), who emphasized the ethics and power reflected in ancient and indigenous stories within Latin American narrative movements. Studies have shown that oral narratives, whether told during community gatherings, conveyed through embroidered fabrics, or shared on digital media, serve to affirm ethnic identity, maintain collective memory, and transmit ethical values (Homer, 2020). For example, Langdon (2018b) explores in his study the value of the narratives of the Siona Indians of Colombia, highlighting how these stories articulate cultural heritage and guide the group’s ethics. Likewise, it has been demonstrated how narrative reconstructions of the myths of the “Bribri” also help communities recover their past, even though these stories are difficult and painful (Nygren, 1998).

For these reasons, storytelling further strengthens community ties and supports emotional expression (Homer, 2020). Traditional methods, such as the transmission of knowledge from elders to youth and ritual storytelling, coexist with modern adaptations, including bilingual storytelling and arts-based projects (Falconi, 2013). The studies reviewed consistently demonstrate that storytelling not only preserves ancestral languages and traditions but also fosters emotional healing, cultural resilience, and a dynamic response to contemporary challenges. On the other hand, Quezada et al. (2018) analyze the cultural values embedded in narratives about the relationship between indigenous groups and nature, emphasizing the importance of values transmitted from one generation to the next for community identity. Meanwhile, the emotional and political power of storytelling is evident in Muzio’s (2018) review, which examines the interaction between music and politics in Latin America during periods of revolution. Furthermore, Shangguan (2020) analyzes the film “Coco” and its use of narrative techniques, visual elements, and indigenous music to evoke emotional resonance in Mexican audiences. This demonstrates how the art of storytelling can evoke strong emotional responses and foster cultural connections.

2 Storytelling is an Anglicism that is not yet recognized by the RAE, but it is used for its meaning “narration of stories,” or simply narration, as well as the act of transmitting stories using words or images (Echazú & Rodríguez, 2018).

In Ecuador, during the pandemic, González-Cabrera et al. (2023) used digital storytelling in a pre-experimental study, collecting digital narratives on the website “Diarios de la COVID-19” (COVID-19 Diaries). The results demonstrated the importance of incorporating artistic resources into narratives to prevent health problems, as well as the mediating role of narrative transport and identification with characters in the perception of risk during health crises.

In the fields of anthropology and sociology, storytelling is used in conjunction with drawing in the participatory mapping technique. This strategic tandem helps identify how community actors interact with their environment. In their study, Herlihy and Knapp (2003) analyze the development of participatory mapping in Latin America, with a specific focus on the Amazon, emphasizing the involvement of the local population in research and applied work. The authors emphasize that this participatory approach reflects the importance of indigenous voices and perspectives in cultural expression. Consequently, storytelling serves as a powerful tool for cultural and emotional expression among the indigenous peoples of Latin America. Through ancient and indigenous stories, music, film, and participatory mapping, indigenous communities can preserve their cultural heritage, affirm their identities, and evoke strong emotional connections within their communities and beyond.

1.4 Drawing as a visual tool for conveying learning and emotions

Drawing is a symbolic representation tool that allows individuals to express ideas, emotions, and knowledge nonverbally (de Miguel y Menéndez, 2020). In indigenous communities, this practice not only has aesthetic value but also fulfills deeply rooted communicative, ritual, and pedagogical functions (Patiño, 2020). In intercultural education contexts, drawing facilitates the transition between diverse cultural languages and promotes forms of learning linked to observation, collective memory, and sensory experience. Far from being a secondary activity, drawing acts as a means of connection between the subject’s inner world and their symbolic environment, facilitating the transmission of ancestral knowledge (Beltrán & Osses, 2018; Fernández, 2021). Various studies concur that drawing facilitates the processing of emotions that are difficult to verbalize and constitutes a form of cultural resistance to hegemonic models of literacy (Gutiérrez et al., 2023; Santos et al., 2020). Studies conducted among indigenous peoples in Peru and Ecuador have shown that spontaneous drawings by children reveal not only their own narrative structures but also visual forms of organization of territory, the body, and family relationships (Chaumeil, 2012; Quezada, 2022). Thus, drawing becomes a privileged channel for articulating identity, belonging, and affection, especially in indigenous childhood, where the visual dimension of knowledge plays a leading role (Grubits & Vera, 2005).

In this context, the present study defined its objective as follows: to identify whether storytelling is a valid tool for Achuar youth to express their emotions more freely and affirm their cultural identity through narratives accompanied by artistic drawings.

2.

Method

The research was conducted using a qualitative approach with a narrative-ethnographic design, within the framework Participatory Action Research (PAR) (Hernández & Mendoza, 2018). This design is characterized by actively involving participants, as is the case here with the Achuar indigenous youth. The key aspect of this methodological strategy is that participants generate information rich in symbolic and contextual content while respecting their worldview, emotions, and forms of expression. In addition, this method had a narrative and ethnographic component, promoting the documentation of cultural practices from an internal (emic) perspective (Mostowlansky & Rota, 2020) through narratives, with cultural and creative mediation tools, suitable for intercultural environments where the objective is both to understand and strengthen indigenous cultural processes.

2.1. Sample and fieldwork

The fieldwork for this research was conducted in the Achuar community of Wasakentsa, which was accessible after a 40-minute flight from Macas, a city located in the Morona Santiago province, in the Amazon region of Ecuador. This community is home to the Salesian mission, which promotes the Wasakentsa Support Center, an institution dedicated to the comprehensive education of Achuar youth based on principles of respect and the strengthening of their culture and traditions.

Figure 1

Location of the Salesian Mission of Wasakentsa

Source: Google Maps

Sampling was conducted at the convenience of the study, which, according to Hernández and Mendoza (2018), allows for the opportunity to take advantage of a situation to obtain information. In this case, thanks to the EPSULA project, in which Salesian researchers and researchers from the University of Azuay participated, it was possible to enter the Salesian mission in Wasakentsa and count on the participation of 18 students who were in their last year at the support center. Although the sample is small, it responds to an ethnographic approach where the symbolic depth of the analysis takes precedence over statistical generalization.

2.2. Procedure

The work was carried out in two stages. First, taking Langdon’s work (2018a) as a reference, a workshop focused on the art of storytelling was implemented, with the aim of familiarizing 18 Achuar students with narrative techniques related to character creation, the use of narrative voices, and the recognition of the educational, cultural, and tourist potential of storytelling. They were also shown how to accompany their narratives with drawings that provide context and allow the audience to imagine themselves as part of the story. During the workshop, examples of audiovisual narratives were shown, highlighting the use of music, nature effects, and other elements. Then, working groups were formed, in which students wrote their own stories accompanied by illustrations. It is worth noting that the adult participants in the study completed the informed consent form and provided their authorization for the use of images.

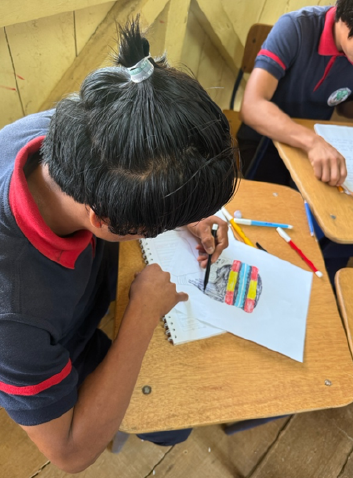

Figure 2

An Achuar student draws on the traditional crown used in his community for ritual acts.

Subsequently, the students shared their stories orally with their classmates, presenting the drawings they had created and explaining the visual elements they had incorporated. They also reflected on the meanings they wished to convey through their stories.

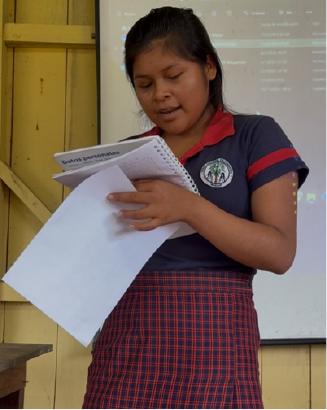

Figure 3

An Achuar student reads her storytelling to her classmates.

Finally, in a second phase, a narrative analysis was applied to process the qualitative data, following the guidelines proposed by Hernández and Mendoza (2018). This analysis examined the internal structure of each story, the portrayal of characters, the events narrated, and the language employed. Likewise, the narrator’s position within the story was taken into account, recognizing how the narrative voice is constructed and its relationship to the expressed content. It is worth noting that this tool was previously introduced during the workshop as part of the storytelling training strategies.

3.

Results

3.1. General description

The group work process was interesting; boys and girls did not work together, as the authorities at the Support Center indicated that one of the rules is to keep them separate. This is because the Achuar culture is very formal when it comes to maintaining friendships and romantic relationships. One of the volunteers indicated that “on more than one occasion, smiling more than once at an Achuar teenager has been misinterpreted; they interpret it as falling in love.” Likewise, parents have requested that special care be taken because young people, when interacting, can form couples and not complete their education. It is essential to note that the students reside at the mission and only return home twice a year, which is a day or more’s walk from the Salesian mission. On the other hand, the behavioral and attitudinal differences between the genders were very significant. Although the teenage girls were more dedicated to their work, they felt more uncomfortable speaking in public. When asked how they felt and what emotions they experienced while writing and remembering about a particular tradition, they felt intimidated. This happened much less to the male students. A worker at the Support Center noted that, culturally, Achuar women typically do not express or discuss their feelings and emotions openly.

3.2. Cultural connotations and elements of nature represented in the stories and drawings

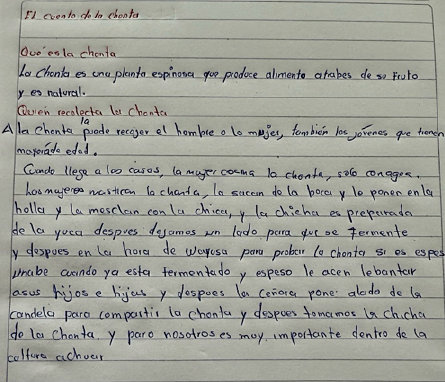

The analysis of the letters and drawings produced by the Achuar students, complemented by the oral presentations recorded on video, revealed a profound representation of the natural environment and the cultural elements central to their identity. The stories reflect a symbolic understanding of the world that does not separate the human from the natural, but instead conceives them as integrated dimensions. The findings are presented below, organized by each production. In “The Tale of the Chonta” (see Figure 4), the story presents a comprehensive view of the plant’s use cycle, integrating ecological, social, nutritional, and symbolic aspects. Unlike a mere botanical description, the text articulates the collection, preparation, consumption, and cultural meaning of the chonta as an integrated system of ancestral knowledge. The narrative begins by defining the chonta as a “spiny plant that produces food through its fruit,” highlighting its natural character and practical usefulness. It mentions that its collection can be carried out by men, women, or young people who have reached the age of majority, which denotes a flexible but regulated distribution of roles based on age and maturity.

The story becomes more detailed when describing the preparation process, which is attributed exclusively to women. The fruit is cooked only with water, then chewed and mixed with chicha made from cassava. This act of chewing—also present in the preparation of traditional chicha—involves a form of natural fermentation that uses saliva as an activating agent, linking the female body to the transformation of food. The mention that women “take it out of their mouths and put it in the pot” reveals a precise knowledge of the technique and a cultural acceptance of processes that in other worldviews might be taboo.

Next, the moment of fermentation is mentioned, and how it is evaluated during the hour of the wayusa, a community gathering in the early morning where knowledge, dreams, and hot drinks are shared. There, the thickness and flavor of the fermented chonta are analyzed collectively, as part of a ritual of validation and appreciation. If the drink is ready, the woman wakes her children to share it as a family and places it “next to the fire,” reinforcing the collective, warm, and symbolic nature of consuming it together.

This story not only describes a type of food but also embodies ancestral technology, gender relations, spiritual practices, and community pedagogy. The chonta palm does not appear as a simple plant resource, but as a cultural element laden with meaning, bringing generations together, symbolizing women’s work, and affirming the continuity of Achuar traditions. The drawing accompanying this story reinforces this vision, depicting the chonta palm with botanical precision. It highlights its thorny trunk and fruits, connecting the symbolic with the visual, and the technical with the emotional.

Figure 4

The Tale of the Chonta

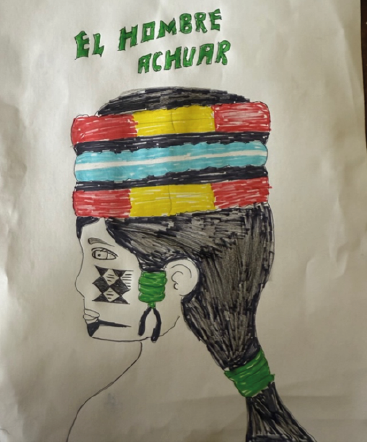

In “The Meaning of the Achuar Crown” (Figure 5), the student clearly explains the symbolic and cultural value of this traditional piece, worn by men on ceremonial and leadership occasions. The crown is often described as a symbol of power, respect, and wisdom, reserved for specific figures within the community, such as wise men, elders, warriors, or individuals with spiritual authority. The account emphasizes that wearing the crown is not a decorative act, but a ritual practice laden with meaning, as it “represents the culture of the Achuar people.” In addition to its aesthetic and ceremonial dimension, the account highlights that the crown appears in key contexts such as meetings, celebrations, or traditional rites. Its use communicates identity, belonging, and status. The text explains that “when someone wears the crown, it is known that he is a true Achuar,” which reveals the strong social value attributed to it as a visual marker of male identity.

However, although it is an object associated with the figure of the man, its existence is deeply linked to the work of women, who traditionally make these crowns with plant fibers, natural dyes, and symbolic elements such as feathers. This duality—the man who wears it and the woman who creates it—reflects a logic of gender complementarity characteristic of Achuar culture, where symbolic power is not constructed in opposition, but in collaboration between male and female roles. The drawing reinforces these meanings by presenting the profile of an Achuar man with typical facial features, ceremonial paint, earmuffs, and a brightly colored crown (red, yellow, blue, green). The carefully delineated visual aesthetic communicates respect and solemnity. The inscription “The Achuar Man” highlights the role of this figure within his community, but also invites reflection on the visual codes that sustain the transmission of identity values.

Figure 5

The meaning of the Achuar Crown.

In “I am chicha” (Figure 6), the narrative adopts a first-person voice from the perspective of the drink itself. This powerful narrative strategy brings to life a central element of Achuar culture. Chicha is presented as an active entity that accompanies people, gives them energy, and participates in key moments of social life. Its tone is proud and affirmative: “I am the drink of Achuar culture.”

One of the most significant aspects of the story is the description of the production process. The narrative explains that the production of chicha is a long process that begins with the planting of the tuber itself. It is prepared from cooked cassava, which is then chewed by women, who initiate the fermentation process with their saliva. This detail, often omitted in external or simplified accounts, shows a deep understanding of ancestral knowledge. Saliva is not seen only as a physical ingredient, but as a symbolic vector of energy, intention, and affection. It is even mentioned that the taste of chicha can vary depending on the woman who makes it, which gives the female body an active role in the sensory and spiritual experience of the food. The narrative also acknowledges that, when fermented longer than usual, chicha can “intoxicate” those who drink it. This characteristic is pointed out without judgment, as part of its potential, although it is noted that some people “get scared” when they learn that it was made with saliva. This mention is revealing as it highlights the intercultural tensions that arise between views that value food as a mediator of relationships and others that analyze it from hygienic parameters or bodily taboos. The student, however, maintains a proud view of the practice, revaluing its legitimacy.

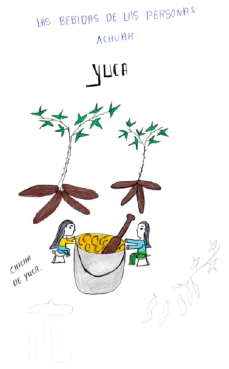

The drawing accompanying the narrative visually reinforces these elements. Two Achuar women are seen preparing chicha in front of a vessel, surrounded by cassava roots and growing green plants. The inscription “people drink me” reaffirms the narrative voice of chicha as an active agent in community life. This story reveals a dense network of relationships between nature (yucca), body (saliva), gender (women), culture (hospitality), and intercultural perception. Chicha, more than a drink, is manifested here as a symbol of resistance, identity, and community, crafted from the body and memory.

Figure 6

I am Chicha.

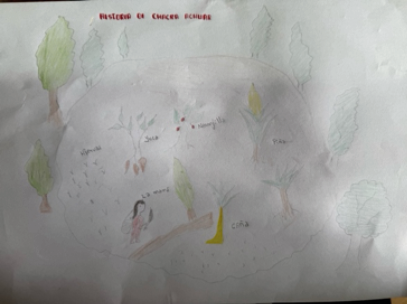

In “The Story of the Achuar Chagra” (Figure 7), the student assumes the narrative voice of the chagra itself, one of the most essential agroecological and cultural institutions in the Achuar world. Through this personification, the idea is conveyed that the chagra is not just agricultural land, but a living being that participates in people’s daily lives and maintains a particularly close bond with women.

The narrative describes how Achuar women sow, clean, and care for the chagra, showing that their role in this space is not only functional but also emotional. It mentions the use of cuttings (sticks) as a method of reproduction, revealing essential technical knowledge: if the “stick” is healthy, it is taken as a seed to be sown elsewhere. This detail indicates an understanding of the plant life cycle and the logic of sustainability that guides land management. Actions such as “peeling the yucca” and “taking it home to cook” are also described, linking agricultural production with food preparation, especially chicha, as suggested in the accompanying drawing. A key phrase in the story is: “If they eat me, people feel happy.” Here, the chagra is presented as a source of emotional well-being, not just nutritional, and as a space of reciprocity where caring for the land produces shared joy. This statement reinforces the Achuar view that the territory is a relational being that, when respected, returns health and happiness to the community.

The drawing complements this narrative with a depiction of the agricultural environment: trees, crops, and people working the land or interacting with it. Although the colors are soft, there is a clear sense of ecological continuity between the natural space and social life. Together, the text and image construct a holistic perspective in which the chagra is simultaneously a territory, a subject, and a mediator of collective well-being.

Figure 7

The story of the Achuar Chagra.

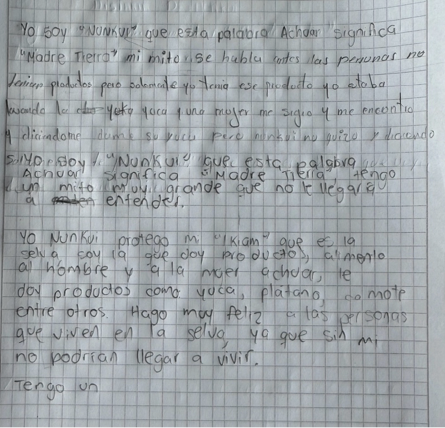

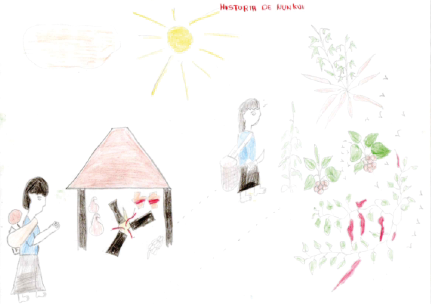

In “The Story of Nunkui” (Figure 8), the student constructs a first-person narrative from the voice of Nunkui, a female entity in the Achuar worldview who represents Mother Earth and protects the jungle territory (Ikiam). The story presents an origin myth that explains how agricultural products, such as yucca, plantains, and sweet potatoes, were initially the exclusive property of Nunkui, who decides to share them with humans after a symbolic encounter with a woman who secretly follows her.

This story embodies a profoundly relational understanding of the world: food, life, and human happiness depend on a living entity that is not viewed as a passive resource, but as an active subject with will, voice, and emotions. Nunkui describes herself as the protector of the jungle, the giver of life, and the guarantor of continuity. The phrase “without me you could not live” sums up her central role in Achuar spirituality, where nature is not a background or an object of use, but the center of the symbolic and material universe. The story also reflects the pedagogical nature of indigenous myths: it explains a cosmological order, reinforces ethical values (respect for the sacred, shared access to goods), and transmits ecological knowledge. Yucca, plantains, and sweet potatoes are not just food, but sacred gifts that must be valued and appreciated. The drawing complements the story with scenes that illustrate the environment and the actions described: a woman carrying firewood, a domestic space with a fire and food, and the jungle’s vegetation, featuring fruits and roots. The figure of the sun and the title “The Story of Nunkui” reinforce the luminous and generative dimension of this mythical figure. The visual composition conveys a balance between humans and nature, as well as an aesthetic that is both everyday and sacred.

This story is particularly valuable for its symbolic power. It combines worldview, myth, gender, and ecology from a child’s and female perspective, showing how Indigenous girls reproduce, interpret, and revalue the ancestral narratives of their people.

Figure 8

The story of Nunkui.

The results obtained show that the stories and drawings created by the Achuar students are much more than mere school exercises; they are symbolic expressions in which ancestral knowledge, daily practices, emotions, and unique narrative structures are intertwined. Each story reveals a particular way of inhabiting and giving meaning to the Amazonian territory, where natural elements such as chonta, chagra, or yuca are not mere objects or resources, but subjects with identity, voice, and relational power. This worldview, strongly marked by respect and reciprocity toward nature, is instilled in children from a young age and finds effective expression in the acts of storytelling and drawing, serving as a powerful vehicle for cultural preservation. Likewise, the stories enable us to discern a cultural logic in which objects, plants, and landscapes are shaped by relationships of gender, spirituality, and memory. The prominent role of women as food caretakers, knowledge bearers, and mediators between nature and community, without requiring narrative centrality, shows how female labor is embedded in the symbolic structure of the Achuar world. In this sense, the act of narrating from the voice of chicha, the chagra, or Nunkui not only conveys knowledge but also produces identity and agency, strengthening the construction of meaning from Indigenous childhoods through an intercultural lens.

3.3. Narrative and symbolic analysis of the stories told by the students

The five narratives created by the Achuar students present a diversity of voices, approaches, and structures. Yet, they share certain fundamental traits that reveal the existence of a distinct narrative framework, where Amazonian worldview, daily experience, and communal knowledge are interwoven. From a formal perspective, one can observe a combination of classical narrative elements—such as the presence of characters, actions, temporal sequences, and resolutions—with resources typical of Indigenous oral storytelling, such as the personification of natural elements, the use of the first-person voice from objects or non-human beings, and a circular or cyclical structure instead of a linear one.

Three of the stories—‘I Am Chicha,’ ‘The Story of the Achuar Chagra,’ and ‘The Story of Nunkui’—employ the narrative device of the first-person voice from a symbolic or spiritual element. In these cases, the narrator is not human, but rather chicha itself, the chagra, or Mother Earth, representing a cultural way of giving voice to the non-human, a characteristic of many Amazonian traditions. This narrative strategy enables students to craft stories that convey respect, intimacy, and reciprocity with their environment, while implicitly questioning the hierarchies of Western logic between subject and object.

In terms of structure, most stories contain a coherent sequence of actions: the introduction of the character or situation, the development of events, and a conclusion or reflection. However, in some of them, the traditional chronological logic is broken, and a more descriptive or explanatory structure is favored—one that focuses more on the meaning of the story than on its temporal progression. This is the case in ‘The Tale of the Chonta,’ where a detailed description of the process of gathering, preparing, and consuming takes precedence over a plot with conflict and resolution. The same occurs in ‘The Meaning of the Achuar Crown,’ which centers on the cultural value of the object rather than on narrative action per se. Thematically, the axes of food, spirituality, gender, territory, and oral tradition clearly emerge. Food appears as a central theme in four out of the five stories (Chicha, Chagra, Chonta, Nunkui), but is always approached from a symbolic standpoint: food is not only sustenance, but also a vehicle for cultural transmission, familial affection, and cosmic order. Gender is evident in both the explicit mention of female roles (the women who prepare, chew, distribute, cultivate) and in the symbolic absence of the male voice in several narratives. In these stories, women do not always speak, but they act, produce, and transmit culture.

Finally, the stories also express a sensitive and internalized view of the territory, where the forest, the chagra, and the food are all part of a single relational fabric. The notion of ‘happiness’ repeatedly appears linked to what is shared, fermented, ritualistic, and collective. This suggests that storytelling, in this context, is not only a means of narration but also a way to preserve, re-signify, and reimagine the world from the perspective of Indigenous childhood.

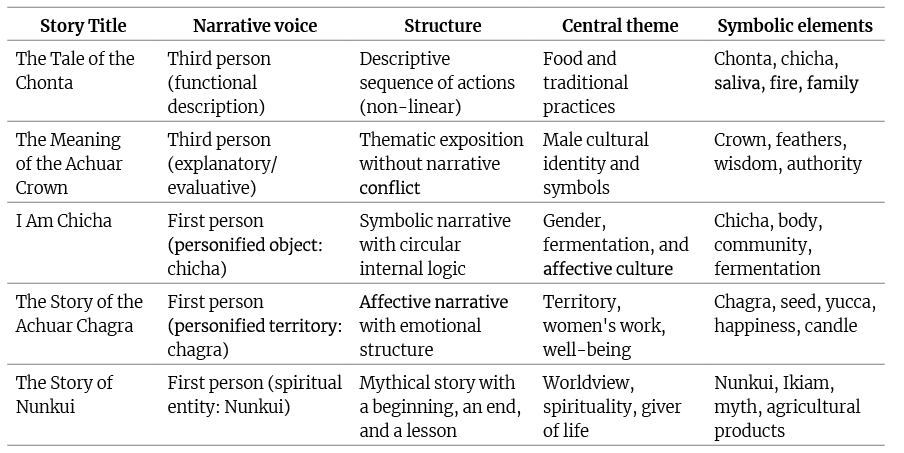

Table 1

Narrative and symbolic summary – Objective B

4.

Discussion

Among the study’s main findings, it is worth highlighting that the stories and drawings created by the students not only expressed cultural and ecological content but also revealed unique narrative structures, complex symbolic strategies, and a strong sense of identity. The analyzed stories demonstrate that Indigenous boys and girls are bearers of profound knowledge about their environment and are capable of articulating this knowledge through expressive forms that integrate orality, visuality, and writing. Recurring themes were identified, including food, territory, women’s labor, ritual objects, and mythical entities, as well as the use of narrative resources such as personification, non-human first-person voice, functional description, and circular logic.

The results indicate that elements of nature—chonta, chagra, the forest, food—were not represented as physical environments or resources, but as living beings that actively participate in community life. This perspective aligns with the theories of authors such as Descola (1996) and Bonilla (2002), who have noted that Amazonian ontologies do not separate nature and culture, but rather conceive of them as interdependent dimensions. Furthermore, the use of elements such as chicha, fire, the crown, or the serpent reveals a dense symbolic network in which the everyday and the sacred are interwoven. This finding is consistent with studies such as Giovannini’s (2015), which documents how the use of medicinal and edible plants among the Achuar is imbued with social, emotional, and spiritual meanings.

Narrative structures were observed that deviate from the classical Western pattern of introduction–conflict–resolution, instead prioritizing description, repetition, metaphor, and personification. This observation is consistent with research by scholars such as Langdon (2018b), who argues that Indigenous peoples of the Amazon develop their own narrative forms, in which storytelling serves not only an informative or aesthetic function, but also pedagogical, ritual, and cosmological purposes. The personification of the chicha, the chagra, and the figure of Nunkui aligns with what Nygren (1998) describes as narratives that not only transmit historical memory but also articulate a unique ethical and cosmological system. This ability to give voice to elements of the environment allows children to construct complex narrative identities, integrating tradition, emotion, and a sense of belonging.

From a gender perspective, the stories reinforce what Descola (1996) and Bonilla (2002) have noted regarding the differentiated but complementary ways in which men and women relate to the symbolic and natural environment. Although Achuar women were more reserved in their oral expressions during the workshop, their stories revealed strong symbolic agency, particularly in the centrality of the female body as a mediator of processes such as fermentation, planting, or connection to the earth. This finding aligns with the contributions of Gutiérrez et al. (2023) on drawing as a form of cultural resistance against hegemonic models of expression.

Moreover, the use of drawing as a support to storytelling, as argued by Beltrán and Osses (2018) and Patiño (2020), was not merely decorative but a fundamental channel for representing narrative structures and symbolic relationships that do not always find verbal translation in Spanish, the participants’ second language. This practice also contributes to what Herlihy and Knapp (2003) refer to as cultural cartography by anchoring an emotional and territorial relationship with the environment in visual form. This exercise enabled students to actively participate in the symbolic reconstruction of their identity, based on everyday experiences transformed into collective narratives. The fact that natural objects like chonta or yuca are narrated with their own voices reflects a worldview in which the environment is not an ‘object of use’ but a ‘relational subject,’ in line with the arguments of Riascos (2007) and Quezada et al. (2018) on the ethical and political value of storytelling in contexts of cultural resistance.

The results confirm that the stated objective was achieved. The use of storytelling accompanied by drawings proved to be a valid and effective tool for Achuar youth to express their emotions more freely and strengthen their cultural identity. Through their narratives and visual representations, the students were able to articulate ancestral knowledge, everyday experiences, and emotional bonds with nature from a symbolic perspective deeply rooted in their worldview. Although gender differences were observed in oral expression, particularly due to the reserve shown by the female participants during presentations, the narrative and graphic content reflected a similar level of symbolic depth and cultural connection across all participants. This experience demonstrates the potential of storytelling as a pedagogical and cultural strategy in intercultural education contexts.

5.

Conclusions

This study aimed to determine whether storytelling, accompanied by artistic drawings, serves as a valid tool for young Achuar students to express their emotions more freely and strengthen their cultural identity. The narratives and graphic representations created by the students not only reflected cultural and ecological content inherent to their worldview but also demonstrated a strong symbolic capacity to articulate tradition, everyday experience, and emotional depth.

The stories revealed distinct narrative structures, non-Western expressive strategies, and a relational view of nature that reaffirms Achuar cultural identity. Furthermore, it was found that the use of drawing as a narrative complement enhanced symbolic expression and helped overcome some of the linguistic limitations posed by Spanish as a second language for the participants.

Although gender-based differences were observed in oral expression, especially among the young women, the content of the stories revealed a significant female role in the transmission of culture, consistent with the logic of complementarity present in Achuar communities.

Consequently, it is concluded that the use of storytelling and drawing constitutes an effective pedagogical and cultural strategy in intercultural education contexts. This experience demonstrates that, when a genuine space for listening and creation is provided, Indigenous children do not merely reproduce ancestral knowledge—they reinterpret it, strengthen it, and project it into the future. It is therefore recommended that these tools be expanded in educational settings that aim to recognize, respect, and promote cultural diversity from an intercultural and decolonial perspective.

While the results are significant, this study presents certain limitations that should be taken into account. The research was conducted with a small sample of students and within a short time frame, which limits the generalizability of the findings to the entire Achuar population or other Indigenous nationalities of the Amazon. Moreover, the narratives were composed in Spanish—a language that is not the participants’ mother tongue—which may have influenced the expressive richness of the texts. However, rather than being viewed as a weakness, these conditions were embraced as part of the study’s ethnographic context: the linguistic and grammatical interferences observed reflect the intercultural transitions experienced by Indigenous children and the challenges involved in expressing themselves symbolically in a foreign language. For this reason, oral, graphic, and written productions were valued as complementary forms of communication that enrich the understanding of their symbolic worlds.

Based on these findings, it is deemed necessary to continue developing educational and methodological proposals that recognize Indigenous narrative forms as legitimate and valuable, not only for strengthening cultural identity but also for enriching pedagogical practices. Promoting the use of native languages in school settings, expanding opportunities for graphic and oral expression, and fostering intercultural exchanges grounded in respect and reciprocity are key actions to ensure that Indigenous children can narrate themselves through their own symbolic codes. This study demonstrates that when a genuine space for listening is offered, Indigenous childhoods not only reclaim traditional knowledge but also reconfigure, reinterpret, and project it into the future.

6.

Acknowledgments and funding

The authors thank the Salesian mission of Wasakentsa, the Salesian brothers, missionaries, volunteers, support center workers, and the students who participated in this study.

This research was carried out thanks to funding from the EPSULA project (Project 101083241) under the Erasmus+ program, co-funded by the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA).

References

Beltrán, J., & Osses, S. (2018). Transposición didáctica de saberes culturales mapuche en escuelas situadas en contextos interculturales. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 16(2), 669-684. https://doi.org/10.11600/1692715x.16202

Bonilla, M. (2002). Machonas y mandarinas: construcción de identidades de género en la Amazonía ecuatoriana. Abya-Yala.

Carpentier, J. (2014). Los Achuar y el ecoturismo: ¿una estrategia sostenible para un desarrollo autónomo? Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Études Andines, 43(1), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.4000/bifea.4391

Chaumeil, J. P. (2012). Una manera de vivir y de actuar en el mundo: estudios de chamanismo en la Amazonía. En P. López (Ed.), No hay país más diverso: Compendio de antropología peruana II (pp. 411–432). Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

de Miguel Álvarez, L., & Menéndez, S. N. (2020). El dibujo como medio en la construcción de conocimiento y proyección de ideas. Revista Sonda: Investigación y Docencia en Artes y Letras, 9, 116-129.

https://doi.org/10.4995/sonda.2020.17859

Deshoullière, G., & Utitiaj, S. (2019). Acerca de la Declaración sobre el cambio de nombre del conjunto Jívaro. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, 105(2), 167–179.

https://doi.org/10.4000/jsa.17370

Delgado, A. D. V., & Ochoa, M. E. O. (2022). Participación política de las mujeres shuar en el Alto Nangaritza, Ecuador. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, (176), 85–100.

https://doi.org/10.15517/rcs.v0i176.52769

Descola, P. (1996). La selva culta: simbolismo y praxis en la ecología de los Achuar. Editorial Abya Yala.

Echazú, E., & Rodríguez, R. (2018). Primer glosario de comunicación estratégica en español. Fundeu. https://lc.cx/ONE31Q

Falconi, E. (2013). Storytelling, Language Shift, and Revitalization in a Transborder Community: “Tell It in Zapotec!” American Anthropologist, 115(4), 622-636. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.12049

Fernández, G. (2021). Saberes ancestrales y ecoalfabetización a través de las artes: una mirada desde/hacia pueblos indígenas en Chile. Revista Chilena de Pedagogía, 2(2), 25-55.

https://doi.org/10.5354/2452-5855.2021.59845

García, J. L. (2004). Artefactos, género e integración comunitaria entre los Quichuas-Canelos de la Amazonía ecuatoriana. En M. S. Cipolletti (Ed.), Artefactos y sociedad en la Amazonía (pp. 161–182). IFEA–IRD.

Giovannini, P. (2015). Medicinal plants of the Achuar (Jivaro) of Amazonian Ecuador: Ethnobotanical survey and comparison with other Amazonian pharmacopoeias. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 164, 78- 88.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.01.038

González-Cabrera, C., González, M., & Bravo, E. (2023). El arte en narraciones testimoniales digitales: Una herramienta persuasiva en comunicación para la salud. Contratexto, 40, 257-277. https://doi.org/10.26439/contratexto2023.n40.6148

Gumucio, C. P. (2002). Religion and the Awakening of Indigenous People in Latin America. Social Compass, 49(1), 67-81.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0037768602049001006

Grubits, S., & Vera, J. Á. (2005). Construcción de la identidad y la ciudadanía en niños indígenas de América Latina. Ra Ximhai, 1(3), 471-488.

https://doi.org/10.35197/rx.01.03.2005.03.SG

Gutiérrez, E., Valor, I., Pérez de Pipaón, G., & Fernández, A. (2023). La proyección de la cultura visual en el dibujo infantil. Un análisis desde la perspectiva de género en Educación Primaria. Observar. Revista electrónica de didáctica de las artes, (17), 116–135. https://doi.org/10.1344/observar.2023.17.6

Herlihy, P. H., & Knapp, G. (2003). Maps of, by, and for the Peoples of Latin America. Human Organization, 62(4), 303-314. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44127812

Hernández, R., & Mendoza, C. (2018). Metodología de la investigación: Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta. McGraw-Hill Education.

Homer, E. (2020). Embroidering Pieces of Place. En L. Leone (Ed.), Craft in art therapy (Primera edición). Routledge.

Langdon, E. J. (2018a). The Value of Narrative: Memory and Patrimony among the Siona. Revista del museo de Antropología, 11, 91-100. https://doi.org/10.31048/1852.4826.v11.n0.21463

Langdon, E. J. (2018b). Dialogicalidad, conflicto y memoria en etnohistoria siona (Putumayo-Colombia). Boletín de Antropología Universidad de Antioquia, 33(55), 56-76. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.boan.v33n55a04

Medina, H. (2002). La organización comunitaria y su papel en la conservación y manejo de los recursos naturales. El caso de la Federación Interprovincial de la Nacionalidad Achuar del Ecuador. Gazeta de Antropología, 18(16).

https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.7404

Mejeant, L. (2001). Culturas y lenguas indígenas del Ecuador. Revista Yachaikuna, (1). ICCI. http://icci.nativeweb.org/yachaikuna/1/mejeant.pdf.

Mostowlansky, T., & Rota, A. (2020). Emic and etic. The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology.

https://doi.org/10.29164/20emicetic

Muzio, R. (2018). Music as Political Actor in Latin America. Latin American Perspectives, 45(6), 171-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X17742899

Nygren, A. (1998). Struggle over Meanings: Reconstruction of Indigenous Mythology, Cultural Identity, and Social Representation. Ethnohistory, 45(1), 31-63. https://doi.org/10.2307/483171

Patiño, K. N. (2020). Escuela y procesos de construcción identitaria en la niñez indígena desde los dibujos en diálogo. Educação e Pesquisa, 46, e237748. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-4634202046237748

Portocarrero, J. (2018). Condiciones de vida y factores socioculturales detrás del riesgo de exposición a metales pesados e hidrocarburos en población indígena amazónica. Anthropía, 15. 25–49. https://doi.org/10.18800/anthropia.2018.002

Quezada, J. J. G., Nates, G., Maués, M. M., Roubik, D. W., & Imperatriz, V. L. (2018). The economic and cultural values of stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Meliponini) among ethnic groups of tropical America. Sociobiology, 65(4), 534-557. https://doi.org/10.13102/sociobiology.v65i4.3447

Quezada, C. Á. (2022). Arte urbano en la interculturalidad: una experiencia artística y pedagógica en una comunidad Kichwa de Ecuador. Ñawi: Arte, diseño y comunicación, 6(2), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.37785/nw.v6n2.a16

Riascos, J. (2007). Ancient and Indigenous Stories: Their Ethics and Power Reflected in Latin American Storytelling Movements. Marvels & Tales, 21(2), 253-267. https://doi.org/10.1353/mat.0.0031

Rios, E.; Carrascosa, MB. (2017). Interpretación morfológica e iconográfica de las cerámicas arqueológicas indoamazónicas y las ceràmicas ceremoniales elaboradas por las culturas Shuar y Achuar de Morona Santiago y Pastaza - Ecuador. Arché, 11(12), 19-26. https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/100932

Santos, M. A., Yavorski, R., Sales, M. V. S., & Buendia, A. P. (2020). El dibujo de alumnos de primaria revelando sentimientos y emociones: una cuestión discutida por la inteligencia emocional. MLS Educational Research, 4(1), 106-121. https://doi.org/10.29314/mlser.v4i1.328

Shangguan, J. (2020). Analysis on the Reasons for the Intensive Resonance Among Mexican of the Film Coco. In 2020 4th International Seminar on Education, Management and Social Sciences (ISEMSS 2020) Dali, China. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.200826.111

Tym, C. (2022). ¿Interculturalidad o “cultura” a lo occidental? El rechazo indígena hacia la educación intercultural bilingüe. Mundos Plurales - Revista Latinoamericana de Políticas y Acción Pública, 9(2), 89–109. https://doi.org/10.17141/mundosplurales.2.2022.5520

Vallejo, I. R. & García, M. (2017). Mujeres indígenas y neo-extractivismo petrolero en la Amazonía centro del Ecuador: Reflexiones sobre ecologías y ontologías políticas en articulación. Revista Brújula, 11. 2-43. https://www.flacsoandes.edu.ec/node/63047

Catalina González-Cabrera,

Catalina González-Cabrera,