Ruth S. Contreras Espinosa

University of Vic - Central University of Catalonia (Spain)

Professor of the Department of Communication. Editor of the journal Obra Digital.

ruth.contreras@uvic.cat

orcid.org/0000-0002-9699-9087

Abstract:

Information and communication technologies are shaped by society but also modified by political structures and it is precisely because of recent technological developments that the debate about their great democratic potential has been updated and stimulated. The idea of an information society has served to open the debate on the democratic principles that should be present in technology. Hence the importance of paying attention to the subject. Linking technologies and democracy implies talking about a wide range of scenarios in which different users, content, and various elements interact.

Keywords

Democracy, Participation, Information and Communication Technology, Digital Technology.

Resumen:

Las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación están moldeadas por la sociedad, pero también modificadas por las estructuras políticas. Y es precisamente por los desarrollos tecnológicos recientes, que se ha actualizado y estimulado el debate sobre el gran potencial democrático que tienen. La idea de una sociedad de la información ha servido para abrir el debate sobre los principios democráticos que deben estar presentes en la tecnología. De ahí la importancia de prestar atención al tema. Vincular tecnologías y democracia implica hablar de un amplio abanico de escenarios en los que interactúan diferentes usuarios, contenidos, y diversos elementos.

Palabras clave

Democracia, Participación, Tecnologías de la información y la comunicación, Tecnologia digital.

Resumo

As tecnologias de informação e comunicação são moldadas pela sociedade, mas também modificadas pelas estruturas políticas. E é justamente por causa dos desenvolvimentos tecnológicos recentes que o debate sobre seu grande potencial democrático tem sido atualizado e estimulado. A ideia de uma sociedade da informação tem servido para abrir o debate sobre os princípios democráticos que devem estar presentes na tecnologia. Daí a importância de se prestar atenção ao assunto. Ligar tecnologias e democracia implica falar sobre uma ampla gama de cenários nos quais diferentes usuários, conteúdos e vários elementos interagem.

Palabras-chave

Democracia, Participação, Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicação, Tecnologia Digital.

Unlike high-risk technologies, information and communication technologies are a systemic network technology that generates factors that support democracy (Barber 2002). All those innovations that involve networks and services have expanded their capabilities and reduced the cost of transmitting voice, video, text, data and images in real time. They have even convincingly demonstrated the full potential to reshape the organization of society, mainly because ICTs are seen as disputed terrain, sites of discursive struggle, as the focus of activism (Dahlberg, 2011) and as educational spaces.

Technology is shaped by society but it is also modified by political structures (Werle 2000). And it is precisely because of recent technological developments that the debate on the great democratic potential of information and communication technologies (ICT) has been updated and stimulated. The idea of an information society has also served to open the debate on the democratic principles that should be present in technology. Hence the importance of paying attention to the subject. The interrelation between society and technology is recognized and in the interrelation which economic, social and cultural change processes interact with technological changes. These changes lead to different types of information society, considered democratic. Democratic quality arguably depends on how ICTs are applied, because technology can enable people to obtain the information they need to examine competing political positions and issues, and provide the means for their recording and subsequent aggregation as ‘public opinion’ of elections through electronic voting, web feedback systems, petitions, email, online surveys, etc. (Dahlberg, 2011). It can also allow access to services designed to improve access to education for the disabled or other disadvantaged minorities. Democratic quality can even be the result of a historical accident. For example, the evolution of the Internet and the TCP/IP protocols on which the networks are based. In the beginning, there was no plan to guide the development of the web with the intention of obtaining dividends. It ended up being an accident because there was talks of a democratic dividend of a public domain nature.

According to the authors Catinat and Vedel (2000), everything depends on how public authorities make use of ICTs. Technology is social both in its origins and in its effects (Mackay 1995), and it is not only in the framework of its use, but even in the framework within which technology is designed, which makes them play a crucial role in shaping the democratic quality of ICT.

The social and political importance of ICTs is undoubtedly remarkable. Firstly, the scope and breadth of ICT systems, where information and communication infrastructures and their penetration into society can be considered in an analogous way. The combination of the scope, breadth and degree of penetration of such systems underscores the importance of their democratic quality. These characteristics may be more or less compatible with the values and structures of democracy. Second, it is related to the network nature of ICTs. One of the generic properties of a network technology is interdependence and complementarity. And depending on the design created for users, they have effects that are not limited to just one individual, but also affect all users of those technologies (Iversen et al., 2004). Therefore, all the options regarding its design and use can be evaluated from the point of view of its democratic ramifications.

The importance of information and communication technologies for a democratic society has also been supported by expectations related to the growth and development of the Internet. It is considered that the web facilitates digital democracy, democracy online, and that thanks to it we interact in different contexts (global and local) with different impacts (social, political and personal) and with different objectives (positive and negative). But ICTs by themselves do not strengthen democracy. Their effects largely depend on the purposes for which the technologies are used and are mainly determined by the design of the technologies used, which may be compatible with the general principles of democratic governance (equality, access, transparency, accountability of accounts, etc.). Whether a technology supports or impedes democracy can rarely be directly attributed to the interests and preferences that shape the design process.

The Journal Obra Digital has felt the need to attend to a little-explored area that brings together two important issues in our day to day: ICTs and democracy. Our number 19, corresponding to the months of September 2020 to January 2021, consists of 6 articles in the block of the monograph entitled “Digital uses for the promotion of democratic experiences” and is coordinated by Dr. Jordi Collet -Sabé and Dr. Mar Beneyto-Seoane, both researchers from the University of Vic - Central University of Catalonia. In the articles in this issue, the authors establish a holistic body of knowledge that invites us to reflect and deepen on the different social and educational impacts that have been generated in the process of interaction between technologies and democracy. As experts on the subject, the authors are in a good position to describe the state of the art, reflect on the different processes that take place in different virtual environments, their link to democracy, and the analysis of the social and educational impacts that can be generated in these spaces. Linking technologies and democracy implies talking about a wide range of scenarios in which different users, content, and various elements interact.

I do not want to close this presentation without inviting our readers to check the two miscellaneous articles that make up our number nineteen. The first of them titled the “Netflix as an audiovisual producer: a snapshot of the serial fiction co-productions” and “Participatory learning contexts in secondary school: from presential education to virtuality.”

References

Barber, B. R. (2002). The Ambiguous Effects of Digital Technology on Democracy in a Globalizing World. In Banse, G., Grunwald, A. & Rader, M. (Eds.), Innovations for an e-Society. Challenges for Technology Assessment (pp.43-56). Edition sigma.

Catinat, M., & Vedel, T. (2000). Public Policies for Digital Democracy. In Hacker K.L. & Dijk J.V. (Eds.), Digital Democracy. Issues of Theory and Practice. (pp.184-208). Sage.

Dahlberg, L. (2011). Re-constructing digital democracy: An outline of four ‘positions’. New Media & Society, 13(6), 855–872. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1461444810389569.

Iversen, E., Vedel, T., & Werle, R. (2004). Standardization and the Democratic Design of Information and Communication Technology. Knowledge, Technology and Policy, 17(2), 104-126.

Werle, R. (2000). The Impact of Information Networks on the Structure of Political Systems. In Engel, C., Kenneth H. K. (Eds.), Understanding the Impact of Global Networks on Local Social, Political and Cultural Values. (pp.167-192). Nomos.

Universitat de Vic - Universitat Central de Catalunya (Spain)

Dr. Mar Beneyto-Seoane is an associate professor in the Department of Pedagogy at the Universidad de Vic-UCC. She currently teaches at the master’s degree and the degree of Social Education. Her main fields of study and research are the study of inequalities, inclusion and digital participation in the educational and social areas.

mar.beneyto@uvic.cat

orcid.org/0000-0001-5946-2670

Universitat de Vic - Universitat Central de Catalunya (Spain)

Dr. Jordi Collet-Sabé is a tenured professor of Sociology of Education at the Universidad de Vic-UCC, where he has been the Vice-Chancellor for Research since 2019. He has conducted research and published internationally on educational policies; school, family and community relations; educational equity; family socialization and democracy. He has been Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Education - University College London.

jordi.collet@uvic.cat

orcid.org/ 0000-0001-8526-9997

Abstract:

This monograph invites to reflect and deepen on the different social and educational impacts that have been generated in the process of interaction between technology and democracy. It does so through six articles that share the same axis: reflecting on the different processes that occur in different virtual environments, their link (or not) with democracy and the analysis of the social and educational impacts that are (or not) generated in these participatory spaces. Linking technology and digital democracy implies talking about a wide range of scenarios in which different actors, content, strategies, types of participation, power relations, among many other elements interact. It is in this diversity of areas, elements, actors and effects that this monograph focuses on. The set of articles that we present show how technology and digital democracy interact in different contexts (global and local) and what types of impacts (social, political and personal; positive and negative; etc.) this interaction can generate.

Keywords

Democracy, Participation, Information and Communication Technology, Educational Technology.

Resumen:

El monográfico invita a reflexionar y profundizar sobre los diferentes impactos sociales y educativos que se han generado en el proceso de interacción entre tecnología y democracia. Y lo hace a través de seis artículos, que comparten un mismo eje: reflexionar sobre los distintos procesos que se producen en diferentes entornos virtuales, su (no) vinculación con la democracia y el análisis de los impactos sociales y educativos que (no) se generan en estos espacios participativos. Vincular tecnología y democracia digital implica hablar de un amplio abanico de escenarios en los que interactúan diferentes actores, contenidos, estrategias, tipos de participación, relaciones de poder, entre muchos otros elementos. Es en esta diversidad de ámbitos, elementos, actores y efectos en la que se centra el presente monográfico. El conjunto de artículos que presentamos nos muestran como tecnología y democracia digital interactúan en distintos contextos (globales y locales); y qué tipos de impactos (sociales, políticos y personales; positivos y negativos; etc.) puede generar esta interacción.

Palabras clave

Democracia, Participación, Tecnologías de la información y la comunicación, Tecnología de la educación.

Resumo

Esta edição convida a refletir e aprofundar sobre os diferentes impactos sociais e educacionais que têm sido gerados no processo de interação entre tecnologia e democracia. E o faz por meio de seis artigos que compartilham o mesmo eixo: refletir sobre os diferentes processos que ocorrem nos diferentes ambientes virtuais, sua (não) vinculação com a democracia e a análise dos impactos sociais e educacionais que (não) são gerados nesses espaços participativos. Vincular tecnologia e democracia digital implica falar sobre uma ampla gama de cenários nos quais interagem diferentes atores, conteúdos, estratégias, formas de participação, relações de poder, entre tantos outros elementos. É nesta diversidade de áreas, elementos, atores e efeitos que esta edição se concentra. O conjunto de artigos que apresentamos mostra-nos como a tecnologia e a democracia digital interagem em diferentes contextos (global e local); e que tipos de impactos (sociais, políticos e pessoais; positivos e negativos; etc.) esta interação pode gerar.

Palavras-chave

Democracia, Participação, Tecnologias de informação e comunicação, Tecnologia educacional.

Beyond the official definition of democracy as a political system, John Dewey already stated a century ago that democracy is, above all, a horizon of life in common where people live the experience of facing challenges, conflicts and complexities of everyday life, together. In this vision of democracy, the objective is not to get rid of others understood as a barrier, as an annoyance or as a simple instrument of own individual fulfillment, but to co-construct with others a new reality in common, shared, diverse, more equitable, fairer and freer. Today, the different online environments have become an integral, daily and significant part of the lives of individuals, families, groups and societies. In this monograph, we ask ourselves about the role of these various digital environments as facilitators or impediments of experiences of authentic democracy.

Specifically, this monograph raises different questions and unresolved challenges, all of them linked to the digital sphere and the concept of democracy. The set of articles presented provide reflections and analysis from perspectives related to digital participation from a broad perspective (such as social and political participation), to more specific perspectives (such as participation in educational contexts). In addition, the articles in the monograph also offer us theoretical and empirical approaches that analyze how the digital world is evolving more and more as a participatory space and, at the same time, how participation spaces have been increasingly digitized. The monograph invites to reflect and deepen on the different social and educational impacts that have been generated in the process of interaction between technology and democracy. It does so through six articles that share the same axis: reflect on the different democratic processes that occur in different virtual environments and describe the social and educational impacts that are generated in these participatory spaces.

In the first article entitled “Digital technologies, big data and ideological (neoliberal) fantasies: threats to democratic efforts in education?”, Dion Rüsselbæk reflects on the phenomena linked to digital technologies and big data, and on the impacts that these generate in democracy in the educational context. It does so by using the work of Jacques Rancière, Slavoj Žižek, and Gorgio Agamben. In the article, the author indicates that a form of instrumental power based on digital technology and supported by neoliberal ideological fantasies tends to eliminate or exclude certain democratic aspects of education.

Next, in the article “Democratize digital school governance: action research results”, by Mar Beneyto-Seoane and Jordi Collet-Sabé, the results of a doctoral thesis are presented. The educational impact generated by the democratization of participatory and digital processes introduced in the school context and in the educational community is described. The main results of the research show us that democratizing school digital participation modifies school power relations, can increase spaces for digital participation, improves the digital competence of the different members of the school community, and can contribute to reducing the digital and educational divide.

Raquel Tarullo, in her article “Informative habits and online participation: a study about young undergraduates in Argentina”, analyzes quantitatively and qualitatively the information habits of university students in Argentina. The intention of the study is to determine the sources of news consumption of young people, and the use of the interaction tools of social networks. The most relevant study results describe the information stages of the students, their digital information environments and the habits or uses that they develop in the digital context.

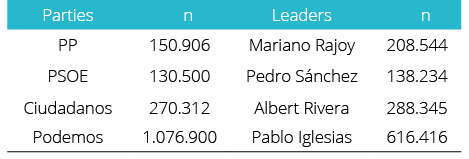

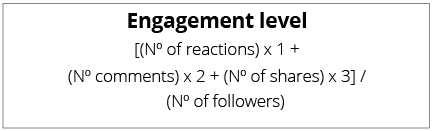

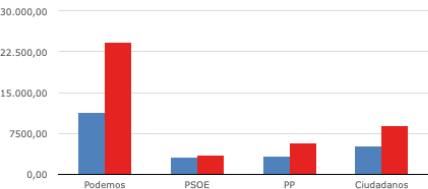

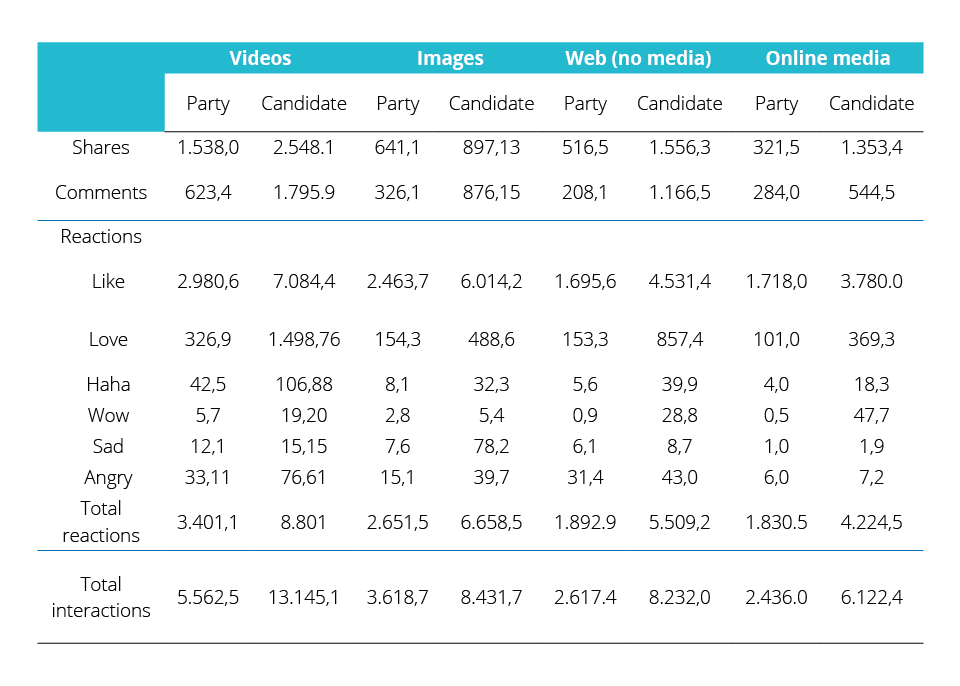

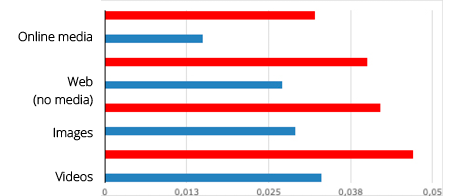

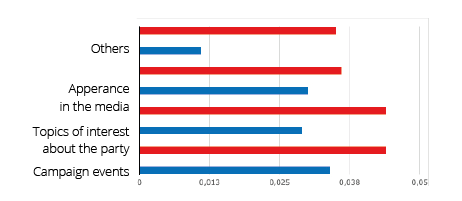

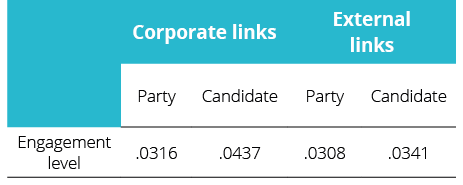

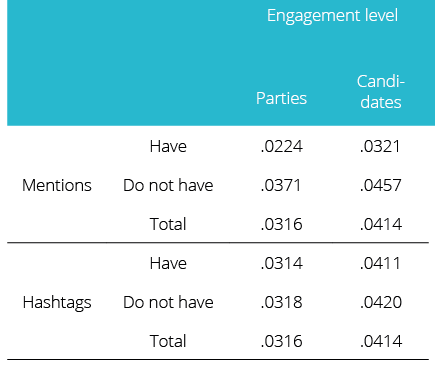

In the following article, “Engagement between politicians and followers on Facebook. The case of the 2016 general elections in Spain”, Susana Miquel-Segarra, Amparo López-Meri and Nadia Viounnikoff-Benet mainly raise the type of interactions and engagement that some Spanish political parties generate on Facebook, the differences in interaction according to the type of content that political parties and candidates publish on Facebook, and the role of hashtags and mentions in the posts they publish on this social network. The main results show that, although there are significant levels of digital interaction, the degree of engagement is low.

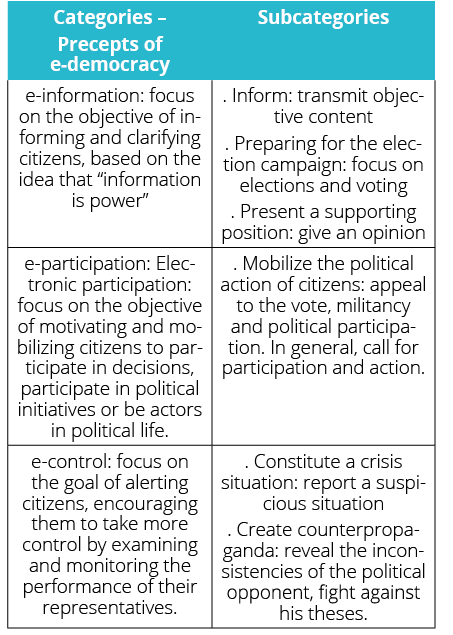

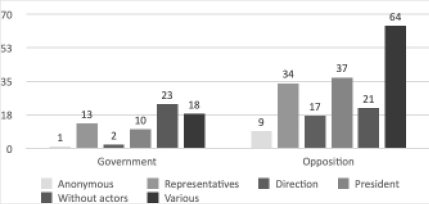

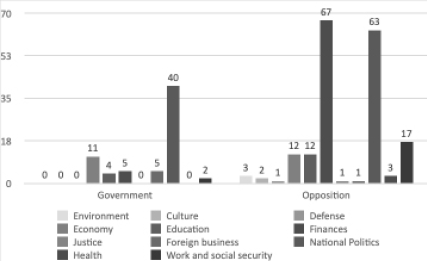

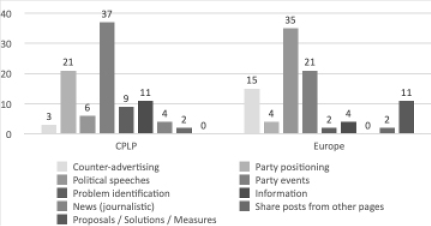

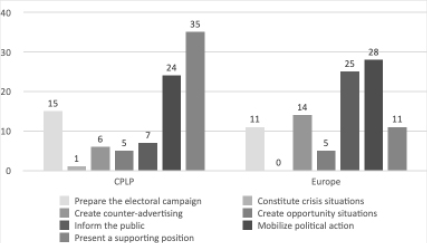

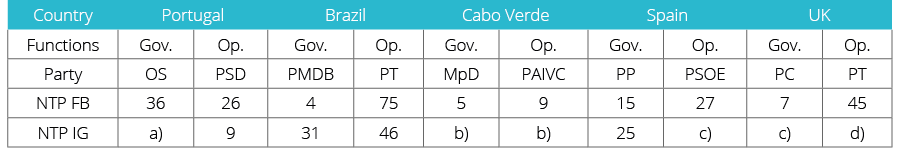

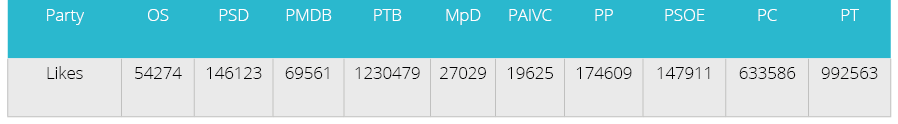

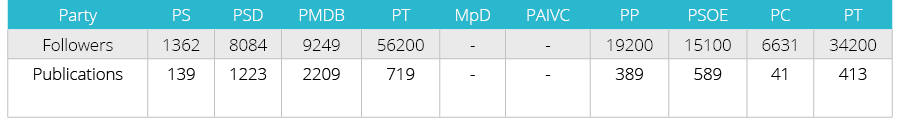

Continuing with the thread of digital uses in the framework of political parties, Célia Belim in her article entitled “Has the digital environment been democratized?”, presents us with an analysis on how digital political communication influences democratic rules. Specifically, the article focuses on studying the digital uses in social networks and in the non-electoral period of government and opposition parties of various countries with full democracy and imperfect democracy in Europe and in the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP). The main results of the study show differences in digital paradigms, objectives, content and uses between opposition parties and government parties.

To close the monograph, Cristian Castillo in his article “Simplicity in public administration and improvement of democracy” analyzes the digital experience of the government of Ecuador in relation to its public policy. To do so, the article reflects on the concept of democracy and its quality. Specifically, the study shows the impact of the implementation of digital strategies and channels on administrative procedures and processes. The main results of the research show that the use of digital media could help improve the quality of a substantive democracy.

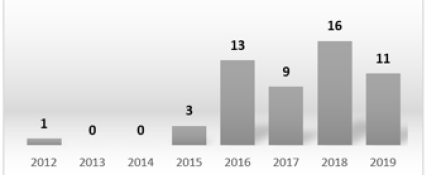

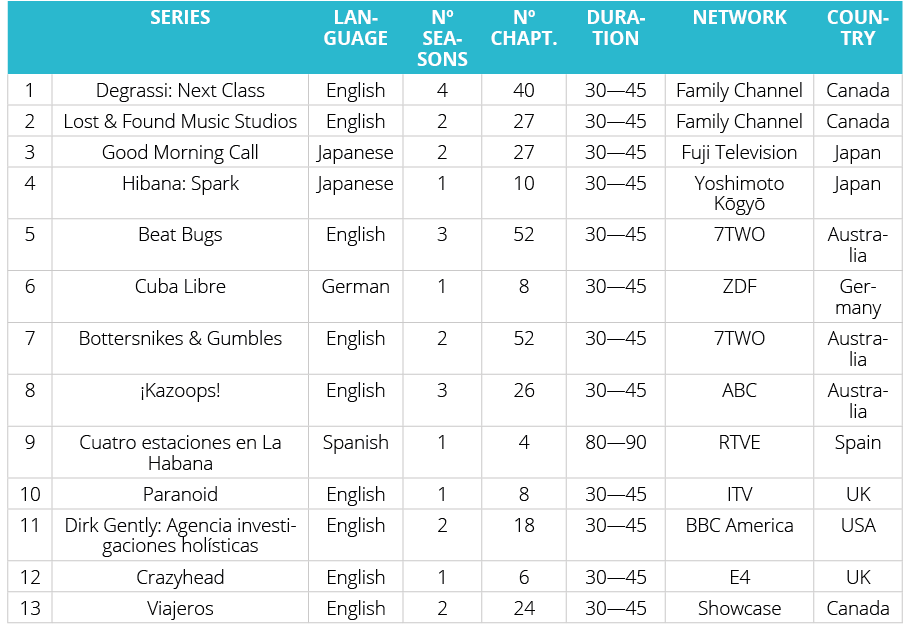

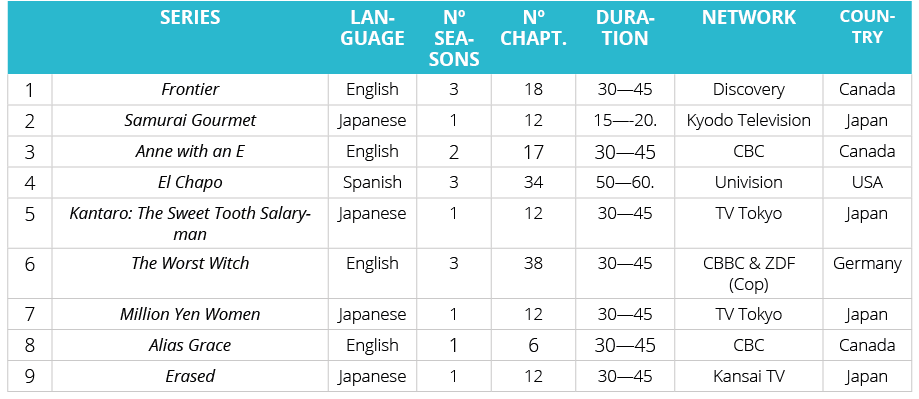

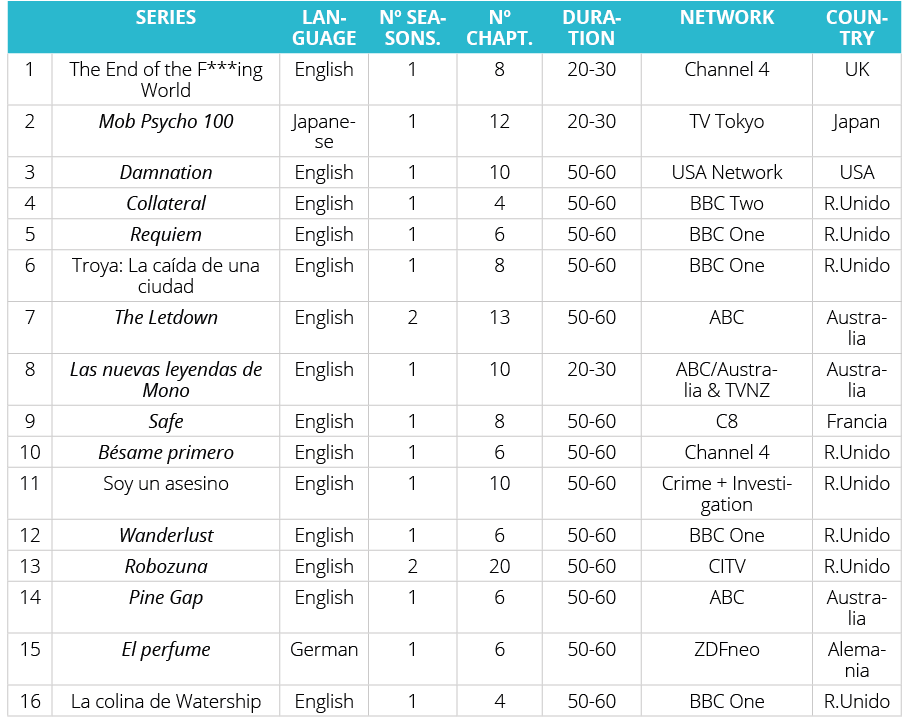

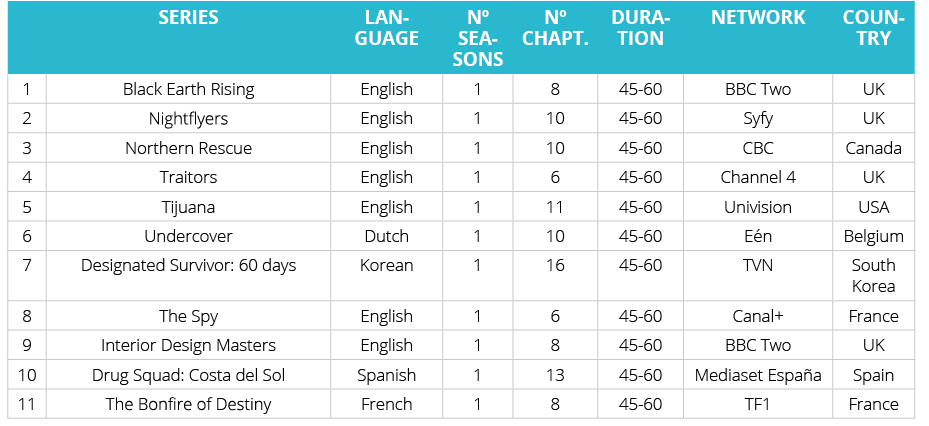

To close this issue of the journal, two miscellaneous articles are presented. In the first, entitled “Netflix as an audiovisual producer: a snapshot of the serial fiction co-productions”, Tatiana Hidalgo links the technological phenomenon derived from the streaming of the NETFLIX platform and its cultural dimension. That is, the audiovisual platform’s way of producing and the user’s way of consuming. Specifically, the study reveals the current importance of recognizing the supply-demand strategy applied by the large audiovisual platform NETFLIX. Another relevant aspect of the article is the description of this strategy, from which we highlight some results such as that the co-production of serial fictions on the platform that manages to involve more participants in the creative process, lowers costs, enhances the development of local fiction and gives importance to minority markets, among others.

The second article in the miscellany (and the last article in this issue of the Obra Digital Journal), is entitled “Participatory learning contexts in secondary school: from presential education to virtuality”. In this article, framed in the thesis of Laura Farré-Riera, it is proposed how to conceptualize the participation of students in secondary education, what aspects condition the participation of students in the school context and what elements should be considered in a non-presential educational context or, in other words, in an online format. A main aspect highlighted by the author is that, despite the fact that there is a certain belief that the modality (presential or virtual) determines the active participation of the students, in reality this participation is strongly conditioned by the pedagogical model that exists in the educational center.

University of Southern Denmark (Denmark)

Associate Professor. Department for the Study of Culture.

dion@sdu.dk

orcid.org/0000-0002-7297-8986

RECEIVED: January 10, 2020 / ACCEPTED: May 08, 2020

OBRA DIGITAL, 19, September 2020 - January 2021, pp. 15-28, e-ISSN 2014-5039

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25029/od.2020.260.19

Abstract

Many fantasies hold that digitalisation can construct democratic spaces for discussing experiences about educational matters. However, based on thinkers such as Rancière, Žižek and Agamben, it is argued that increased big data production in education through digitalisation does not support such democratic spaces. Instead, it mirrors a neoliberal fantasy and a form of instrumentarian power that distributes the sensible in mechanical (numerical) ways. Democracy in education is at risk of being dismantled by perceptions that democratic conversations and struggles are unproductive and do not contribute to the desired numerical visualization of learning results, achievements and competitiveness of students.

Keywords

Distribution of the sensible, Instrumentarian power, Numerical imagination, Digital pictures.

Resumen

Muchas fantasías sostienen que la digitalización puede llegar a construir espacios democráticos con el objetivo de discutir experiencias sobre asuntos educativos. Sin embargo, pensadores como Rancière, Žižek y Agamben, argumentan que el aumento de la producción de big data en la educación a través de la digitalización no es compatible con los espacios democráticos. En cambio, refleja una fantasía neoliberal y una forma de poder instrumental que distribuye lo sensible de manera mecánica (numérica). La democracia en la educación corre el riesgo de ser desmantelada por la percepción de que las conversaciones y las luchas democráticas son improductivas y no contribuyen a la visualización numérica deseada por los resultados de aprendizaje, los logros y la competitividad de los estudiantes.

Palabras clave

Distribución de lo sensible, Poder instrumental, Imaginación numérica, Imágenes digitales.

Resumo

Muitas fantasias sustentam que a digitalização pode construir espaços democráticos com o objetivo de discutir experiências sobre temas educacionais. No entanto, pensadores como Rancière, Žižek e Agamben argumentam que o aumento da produção de big data na educação por meio da digitalização não é compatível com os espaços democráticos. Em vez disso, reflete uma fantasia neoliberal e uma forma de poder instrumental que distribui mecanicamente (numericamente) o sensível. A democracia na educação corre o risco de ser desmantelada pela percepção de que as conversas e as lutas democráticas são improdutivas e não contribuem para a visualização numérica desejada pelos resultados de aprendizagem, as realizações e a competitividade dos estudantes.

Palavras-chave

Distribuição do sensível, Poder instrumental, Imaginação numérica, Imagens digitais.

1. INTRODUCtioN

Problematizing digitalisation is a ‘risky business’ as many fantasies are attached to the phenomenon. Digital technologies seem to be both inevitable and necessary if we are to be able to cope with the destined future. However, what future is that? We, as human beings, play vital parts in the future through the ideas, beliefs and convictions in which we invest. That said, the future is not a coming event. It has already arrived, so to speak, not in a finished form but in an unfinished form. Critically engaging questions about the future requires reflecting on what influenced them in the past and the present and how ideological fantasies about the future also influence them. To problematize our contemporary modus operandi, (what we do to cope with the future), we must focus on how the past, present and future are always intertwined so that no final endings or beginnings exist.

We must bear in mind that the future is being used to support many investments made to digitalise modern societies. Powerful forces such as politicians and private corporations exploit altruistic arguments to legitimise digital investments. The arguments sound like the following. Digitalisation has the potential to strengthen future democracy by allowing people to connect, communicate and share information with each other. Digitalisation can be used to install order and harmony in a disorderly, inharmonious world. Digitisation can bring more transparency to matters such as what goes on in state institutions, so nothing is hidden from politicians and the public.

It is difficult to deny that digital media such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter can facilitate political conversations from which democratic agoras (public spaces) can emerge and lead to live action. Consequently, such media can be (and have been) used to mobilise demonstrations such as Occupy Wall Street, a protest against economic inequality and the power of financial institutions. Digital media can play vital roles in political changes, as we have seen in the Middle East (e.g. the Arab Spring), and they can support non-profit organizations that advocate democracy, human rights and enlightenment. Here, we can mention the organization Ideas Beyond Borders, whose purpose is to empower individuals oppressed by totalitarian regimes by giving them access to, for example, online information, knowledge and perspectives that can support critical thinking, engagement and democracy (see https://www.ideasbeyondborders.org).

However, we must not forget that digital media regulate and structure the conversations that can take place in such agoras, thereby possibly (re)producing different inclusion and exclusion mechanisms. For example, if we do or say something that does not meet specific standards, norms or values, we might be put in jail. That is, blocked and excluded from participation by Facebook. Our freedom to communicate with others as democratic citizens thus “is strictly prescribed by the coordinates of the existing system” (Žižek, ٢٠١٩, p. ٤) and the underlying logic that frames and structures this system. Digital media are not only public spaces or agoras in which we, as free human beings, can communicate in democratic ways. Digital media are also spaces in which big data and information about others and us are collected and produced. Big data, though, is a contested term that has many meanings and can be produced and used in many ways. As Williamson states, it is “simultaneously technical and social” and has “the power to change how and what we know about society, the people and institutions that occupy it” (Williamson, 2017, p. xi). Furthermore, myths, ideologies and fantasies of objectivity are attached to big data and are being used for political purposes (Jurgenson, 2014).

Collection of big data about our behavioural activities sustains what Zuboff (2019) calls instrumentarian power. This form of power mirrors an ideological fantasy (Žižek, 2008a) that human behaviour can be engineered and predicted by scientifically generated data, numbers and statistics. This fantasy supports a utopian desire for societal safety, harmony and order. Moreover, it sets aside subjective idiosyncrasies and transcends the uniqueness of particular contexts. It thus installs automated decision-making, freeing us from the burden of decision-making. That is, from the tyranny of choices that can “increase our anxiety and feeling of inadequacy” (Salecl, 2010, p. 15). We presume that by relying on big data and digital technologies, we can avoid such burdens and can be guaranteed certain outcomes. In other words, there is a strong belief that we can use big data to figure out things (e.g. how to learn in the most effective way) and produce risk management strategies to protect ourselves from unpleasant surprises such as “our absence of completeness”. However, many factors (e.g. ethics, mind-sets and values) cannot be studied and understood by relying only on big data and the patterns and correlations that seem to exist between different sets of data (Eynon, 2013; Herzogenrath-Amelung, 2013).

Big data, though, remains widely used. It is closely connected to the well-described neoliberal agenda in which comparisons, transparency and competition are seen as means to make humans, public institutions and private organizations more efficient and productive (Harvey, 2007; Mau, 2019). Brown (2015) stressed that a particular form of reason configures political and democratic matters in economic (measurable and data-based) terms. Brown’s (2015) basic argument is not that the market logic corrupts democracy; instead, she argued that neoliberalism converts political and democratic matters into economic and numeric ones, as Clarke and Phelan (2017), Mau (2019), Rose (1999) and others have also argued. Following Brown’s (2015) line of thought, one of the main threats to democracy is the powerful belief that competition is the driving force within almost all spheres of society, including education. This belief installs a particular logic in which we, as human beings, are understood and must understand ourselves as ‘firms’. This firm logic encourages us to focus on our competitiveness and the value of our capital in the eyes of others. To optimize our positions in the (labor) market, we constantly ask certain questions: How do I look in others’ eyes? How do they see me? What can I do to be seen and heard in ways that increase my capital value? Learning seems to be key here, particularly, instrumental forms of learning that politicians and learning experts can govern, control and measure (Biesta, 2010; Lewis, 2013; Simons & Masschelein, 2007).

Digital surveillance technologies are used in education, often uncritically, as learning management systems to produce, monitor and present big data on, for example, students’ behaviour, well-being (e.g. moods, thoughts and feelings) and learning results. Politicians and the public rely on such data to judge whether schools, teachers and students meet learning expectations and objectives. More than ever, digital technologies govern learning processes in schools and produce huge amounts of data that inform whether learning takes place in the most effectful and productive way.

My ambition in this article is to problematize the phenomena of digital technologies and big data and their impacts on democracy in education. What ideological fantasies are they formed by, and which do they contribute to forming? How do they regulate the distribution of the sensible, and what are the consequences for democracy? I analyse, discuss and reflect on these questions, drawing on Jacques Rancière’s work on aesthetics and politics, Slavoj Žižek’s work on ideological fantasies and Giorgio Agamben’s work on what it means to be a special being and seen as a pure singularity.

Against this background and through examples from different educational contexts, I illustrate how a digitally based instrumentarian form of power supported by neoliberal ideological fantasies contributes to erasing time and space for democratic matters in education. I do not aim to argue against digital technologies. Instead, I argue that we need to free ourselves from the ways in which digital technologies are used to monitor, regulate and produce numerical data about students’ (learning) behaviour, progress and results in school. We, therefore, must set such technologies free from their proper uses and places in education and discuss whether they should and can be used otherwise (Agamben, 2009; Lewis & Alirezabeigi, 2018). If this is to be possible, however, we must be aware of the ways in which digital technologies regulate the distribution of the sensible, as elaborated in the next section.

2. IDEOLOGICAL FANTASIES AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE SENSIBLE

According to Rancière (2004, p. 13), politics and democracy revolve “around what is seen and what can be said about it, around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak, around the properties of spaces and the possibilities of time”. Put differently, a certain form of the aesthetic-political distribution of the sensible installs a regulative (aesthetic) regime that historically determines a priori what is judged as (dis)orderly, what something or someone is described and defined as and what is (in)visible (not) sayable and (not)audible (Rancière, 2004). Within such a regime, “the partition of the sensible is dividing-up of the world”. For example, the division of people and political matters within that world (Rancière, 2010, p. 36). In other words, a regime has consequences for the ways in which our aesthetic sensibilities are framed and the ways in which we engage in various (e.g. political and educational) matters in the world (Sjöholm, 2015). In an education dominated by a digital-data and number regime, as Taubman (2009, p. 52) described it, it becomes difficult to employ vocabularies and concepts that transcend the regime. Consequently, to be deemed legitimate, idiosyncratic and concrete, qualitative and sensible experiences must be translated into and expressed by abstract and quantifiable numbers. What cannot be quantified does not count, and only what can be counted has quality. The more we are convinced that others take such a mechanical and numerical starting point seriously, the more we too take it seriously, and vice versa (Mau, 2019, p. 49).

According to Žižek (2008b), a given regime is ideological par excellence. An ideology relies on a phantasmatic background. Indeed, “the fundamental level of ideology, however, is not that of an illusion masking the real state of things but that of an (unconscious) fantasy structuring our social reality itself” (Žižek, ٢٠٠٨b, p. ٣٠). For example, an ideological fantasy supports a common belief that meaning exists in a ‘meaningless world’ (we only have to find it). In other words, a fantasy provides us an “illusion which structures our effective and real social relations. Thereby, masks some insupportable, real, impossible kernel (conceptualized by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe as ‘antagonism’: a traumatic social division which cannot be symbolized)” (Žižek, ٢٠٠٨b, p. ٤٥). An ideological fantasy makes us believe and act as if a ‘natural’ logic lies behind the structure of social positions and roles within a certain social and symbolic order, although we know that is not the case.

Žižek (٢٠٠٩a) gives us a concrete example of how an ideological fantasy often paradoxically works in our digitalized societies. On one hand, the state and big companies control and penetrate our lives in undemocratic ways, while on the other hand, we find state regulation necessary “to maintain the very autonomy it is supposed to endanger” (Žižek, ٢٠٠٩a, p. ٣٢). In this case, the fantasy conceals this paradox, “yet at the same time it creates what it purports to conceal, its ‘repressed point of reference’” (Žižek, 2008a, p. 6).

I further argue that such an ideological fantasy regulates and contributes to the ways in which the sensible is divided. And a particular division of the sensible can explain why we see and hear persons or things as reasonable or noisy, why we believe there is no opposition or social antagonism between freedom and control (as mentioned) and why we act against our better knowledge that state regulation, control and surveillance that suppress our freedom cannot simultaneously support autonomy and democracy. In other words, we act as if we do not know it, even though we know it. Moreover, fantasy structures our desire. However, do we even know that we desire security, control and regulation along with freedom, autonomy and non-regulation? That is what a given fantasy tells us that we must desire such opposite matters that are seemingly illogical on one level but quite logical on another if we want to live in a democratic society. The point is that ideological fantasies can mask absurd arguments, so we find them reasonable and act based on them as if we really believe in them.

To problematize such a paradoxical fantasy and how it divides the sensible, one must try to observe oneself, others and the world from another point of view. To avoid any misunderstandings, let me state here that we can never grasp reality itself by shifting to a more ‘appropriate perspective’. Every perspective is “always-already framed, seen through an invisible frame” (Žižek, ٢٠٠٩b, p. ٢٩). Something always eludes a given perspective and perhaps can be grasped by another perspective, which in turn produces a void that other perspectives must fill, and so on (Žižek, ٢٠٠٩b). Žižek (٢٠١٤) provides an illustrative example of what it means to problematize a given fantasy by observing a situation from another perspective:

A loss of the phantasmatic frame is often experienced in the midst of intense sexual activity—one is passionately engaged in the act when, all of a sudden, one as it were losing contact, disengages, begins to observe oneself from outside and becomes aware of the mechanistic nonsense of one’s repetitive movements. In such moments, the phantasmatic frame which sustained the intensity of enjoyment disintegrates, and we are confronted with the ludicrous real of copulation. (Žižek, 2014, p. 28)

To problematize such a given phantasmatic frame is difficult. When we begin to disengage ourselves from the activity or game, we might experience a loss of enjoyment as we dissocialize and exclude ourselves by questioning the “mechanistic nonsense” in which we are participating. That might be the reason why we play the digital game even if we know that by doing so, we might support anti-democratic tendencies. This playing might explain why the unequal distribution of roles and positions within a particular classification and categorization regime can be sustained and avoid criticism.

Agamben (2007, p. 59) puts it thus: “The transformation of the species into a principle of identity and classification is the original sin of our culture, its implacable apparatus”. It seems impossible to be an unrepresentable or indistinct, special being free from any determination. Stated differently, it is impossible to participate in communities “without affirming an identity” (Agamben, 1993, p. 86). It is a problem if we are never given the possibility to emancipate ourselves from the classifications and categorizations that ascribe to us certain identities. Moreover, the lack of such possibilities can maintain unequal positions from which we cannot free ourselves.

For example, typifying students is a common practice in the educational field. However, if students never have the possibility to remain “indistinct and unrepresentable and free of any determination to be or not to be set in advance” (Lewis, 2013, p. 41), they cannot be free in a democratic sense. Our ability to see and hear students as special beings—that is, as “more than the sum of their abstracts” (de la Durantaye, 2009, p. 162)—is a basic condition for supporting democratic spaces. If only the few and not all can play different roles and occupy different positions, and this situation can never be reversed (but is irreversible), then time and space for democracy vanish (Rüsselbæk Hansen & Toft, 2020).

Where then are we left? What democratic possibilities exist in a time when ever more things and thus more aspects of our lives are turned into machine-readable data and numbers? What does it mean “to be recognized, if the object of recognition is not a person but a numerical datum”? (Agamben, 2011, p. 53) Before turning to these questions, we need to take a closer look at the contemporary form of instrumentarian power that supports and is supported by the ideological fantasy that produces a contemporary desire for digital technologies and big data.

3. NEOLIBERAL LOGIC, COMPARISON AND OTHERS’ EYES

Today, a mix of state, public and market fields structure the social in complex ways. How this looks is difficult to observe as these fields do not have clear borders between them. Although such borders have never been clear, it still seems reasonable to claim that state politics had a different character in the past than the present. Think, for instance, of Adam Smith’s ideological fantasy of the invisible hand assumed to regulate the market and to automatically achieve equilibrium without any state or government interference. Today, few seem to believe in such an invisible form of regulation. Instead, it is believed that a state-driven, visible hand is needed if we are to learn to act like individuals (not collectives) that are driven to compare, compete and measure ourselves against each other in the market. We seem to need to learn to accept that unreasonable “demands, setbacks, humiliations and failures have to be chalked up to oneself—and we then just have to wait cheerfully for new opportunities” (Nachtwey, 2017, p. 134). Such a logic stigmatizes and disciplines losers and places winners in positions they are so afraid to lose that they fight even harder than before.

Despite the dysfunctionalities this logic obviously produces, a strong belief exists that the market is a special realm in which ‘miracles’ happen. Rhetorically asked: Who wants to say no to miracles? Political initiatives are developed to install what Brown calls a neoliberal governing rationality (a form of state-initiated market logic) into spheres traditionally based on other rationalities, with the following consequences:

both persons and states are construed on the model of the contemporary firm, both persons and states are expected to comport themselves in ways that maximize their capital value in the present and enhance their future value, and both persons and states do so through practices of entrepreneurialism, self-investment, and/or attracting investors. (Brown, 2015, p. 22)

Our competitiveness becomes the overall issue, and we are strictly commodified as homo economicus and homo calculus who can calculate our own (economic) value and that of others. On one hand, we are liberated to enhance our “human capital, emancipated from all concerns with and regulation by the social” (Brown, 2015, p. 108). In a Marxian sense, we are free from ownership and have the freedom to sell our labor power. On the other hand, we are on our own due to the decline of collective solidarity. We possess (pseudo) freedom from all constraints, except the rule of the market. We are encouraged not to act politically but to focus on our individual human capital and the ways in which others can invest in it. I engage with others, but not politically; others are only interesting in so far as they can make me look good in the (job) market. Not every looks count; only the ‘right’ symbolic looks count. Consequently, I must strive to achieve looks derived from valuable symbolic positions. To paraphrase Kant, others are treated not as ends in themselves but instead as (symbolic) means to strengthen my ‘firmability’.

Typical ways of judging the value of others’ capital and our own include data gathering, measuring and comparing. Using numbers allows us to rate and create tables and graphs to make complex (e.g. learning) matters simple and visible. We must not forget, however, that numbers isolate information from their particular contexts and are blind to diversity:

Numbers translate the idiosyncratic, the individual and the unique into universal and compatible codes which effectively strip away all the specifics of the case and, by that very act, make links across temporal and spatial boundaries. (Mau, 2019, p. 34)

The clarity and certainty attached to numbers are nothing more than a fiction supported by an ideological fantasy. Many know that but still act as if it is not the case.

The reason for our ‘number-fetish’ might be that something sublime emerges in numbers and the many assumptions attached to them. First, they are the language of ‘real evidence-based science’. Second, they are magical and mystical because they can simplify complex matters. Third, they come in many disguises such as lucky vs. unlucky, good vs. bad, and value laden vs. neutral. Fourth, they can be communicated by and to almost everyone. Fifth, they can transcend cultural borders and cover up social antagonisms. Sixth, they can tell us about our happiness, intelligence and learning achievements and potential. Thus, we are told by the so-called experts.

But why do we listen to such nonsense? Why do we not act as thoughtful human beings and problematize the ideological fantasy that tells us that numbers possess sublimity? Why do we not mix poison into such a fantasy “in order to increase its degree of toxicity to the limit of what can be survived” (Steinweg, 2017, p. 66)? An answer to this question might be that thinking, despite its advantages, is not always considered to be worth the time spent on it. Thinking is not always pleasant and sometimes is the opposite. Thinking can raise radical doubts and open up unpleasant views on the reality: “Oh, I did not know that!” “Looking at it in this way makes me sad!” “I don’t want to know this, and instead, I prefer to hold on to my pleasant belief!” Moreover, thinking does not guarantee security and requires a break from our ordinary conceptions of reality. Thinking means that one loses oneself and gets “lost again and again” (Steinweg, 2017, p. 2). Consequently, we can be encouraged to not think or poison an ideological fantasy with ‘dangerous’ critical thoughts. Another reason to avoid thinking is that fantasies do thinking for us. Often, they set us free from the burden to think for ourselves. Is that not what phantasmatic numbers do? Is that not the reason why we stick to them and act as if we believe in them even though we know that doing so is problematic?

4. INSTRUMENTARIAN POWER AND ITS EFFECTS

As argued, great interest lies in digitally produced numerical data about each and every one of us. This interest arises from a form of instrumentarian power that seeks products (e.g. digital technologies) designed to “forecast what we will feel, think and do: now, soon and later” (Zuboff, 2019, p. 96). This form of power is inspired by ideas of radical behaviorism and the promise of behavioural engineering and regulation. Radical behaviorism reduces human experiences to measurable, observable behaviors and has no interest in the meanings of experiences such as pain, suffering and joy. Put differently, our mind, soul and (un)consciousness are not of great interest as they cannot be observed, measured or calculated.

Instead, “instrumentarian power aims for a condition of certainty without terror in the form of ‘guaranteed outcomes’ […]. It severs our insides from our outsides, our subjectivity and interiority from our observable actions” (Zuboff, 2019, p. 378). Such a regime of power replaces social trust, meaning and understanding with a focus on digitalisation, mathematical calculations and predictions. Human experiences are dispossessed not only by abstractions of concrete experiences but also by the idea that human experiences are raw material for datafication and numerical descriptions (Zuboff, 2019, p. 233–234).

With this short introduction to instrumentarian power, we can see its similarities to the contemporary form of (neoliberal) governmentality that overturns the traditional hierarchical relation between causes and effects. The reason for this is that “governing the causes is difficult and expensive, [so] it is safer and more useful to try to govern the effects” (Agamben, 2014, p. 2). In the focus on effects, not causes, a certain ideological fantasy is at stake: a fantasy oriented towards “what” questions (e.g. What works? What can be measured?) instead of “why” questions (e.g. Why does it works? Why measure it in the first place?). Asking “what” questions more than other types of questions affects the distribution of the sensible, including in education, as examined in the next section.

5. DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES AND A NUMERICAL IMAGINATION IN EDUCATION

Digitalisation and big data in education, if we follow Han’s (2017b, p. 58) argumentation, “free knowledge from subjective arbitrariness”. In other words, we will not need to rely on our own judgements, perspectives and practical experiences as big data is assumed to be able to tell us what troubles students, what they have learned so far and what one can expect of those with particular habitus and socio-economic backgrounds. In principle, all we have to do is look at and listen to data on students. Using data in this way eliminates the need for critical thinking as it “empties of sense the language itself” (Han, 2017b, p. 59). Consider this example from an ethnographic study on an ordinary English school class. As we are told, at the beginning of a typical day, the teacher asks the students if they have met their individual “behavior-for-learning target last week” (Livingstone, 2014, p. 5). Then, we are told that:

Teachers entered data live into the computer or recorded it on the white board and entered it later. Thus, at the start and end of each day, the students’ data could be read out to the class, making progress or failure visible, and inviting constant reflection on their learning trajectory. Then, behind the scenes, both attainment and behavior are measured, standardized and made available for manipulation. Since class time was heavily occupied in data collection, and since a panopticon-like punishment room awaited those whose record showed too many bad marks, we initially thought the system would be hugely unpopular with the students. But we were wrong, as both youth and parents explained to us. (Livingstone, 2014, p. 6)

The example illustrates how a particular distribution of the sensible takes place. The teacher describes what she sees and hears as important data about each student’s learning, which are presented to the class “at the start and end of each day”. The students are encouraged to focus on their successes, failures and learning progress. As we can see in the field notes, the digital technology (or system) is not unpopular with the students. To the contrary, the students find the standardized system to be fair and helpful as it can tell them whether they are on the right learning track. They believe in the system as it indicates that the school has control over their learning. It is also mentioned that the student behaviour is measured, and the data are “made available for manipulation… behind the scenes”. The aim is to control future forms of behaviour and punish those students whose records show “too many bad marks”. However, what does it do to the democratic space in the classroom when everything that students say and do is recorded and put into a computer as “pure reliable data”? Under such conditions, are students willing to ask critical questions to the social order, norms and values when the teacher and others may judge behind the scenes such questioning as disorderly behaviour and a threat to the school order?

Recording what students say and do in class can be seen as an innocuous, helpful approach, but what makes sense in one concrete context does not necessarily makes sense in another. Therefore, it is not without consequences to try to understand and govern blurry issues from a distance, far from particular contexts. Transforming blurry concrete matters into clear abstract data supports a form of an “oxymoronic numeric imagination”, which can be defined as the predisposition to seek out certain kinds of quantitative explanations that “have little respect for complexity of the actual human world” (Morozov, 2013, p. 260). Instead, the world is assumed to reveal itself through a numerical imagination. Who has the symbolic positions to do the imaginary work is rarely questioned? It seems to happen by itself; the numbers do the job for us. However, that is not the case. As argued, numerical forms of imagination are difficult to resist because they are supported by a powerful phantasmatic frame. When we rely on a numerical imagination, the social is distributed in linear, factual and quantitative ways; displacing other forms of imagination that could transcend such distributions and provide opportunities to imagine, sense and think about persons and things in non-mechanical and numerical ways (Morozov, 2013, p. 260).

Another example we must consider comes from an article in The Guardian, “Under digital Surveillance: How American Schools Spy on Millions of Kids”, published on 22 October 2019. This article illustrates how digital technologies are used in schools in the United States to monitor what students write in their emails, documents and chat messages. If something is considered to be risky and indicates (or is interpreted to indicate) self-harm, bullying or other suspicious matters, schools respond immediately as they are under pressure from politicians and parents to keep students safe and to protect them from themselves, others and the ‘dangerous’ world, if needed.

In the same article, it is argued that monitoring students is important because it prepares them and gives them a “training ground” to learn what monitoring means and what they must be aware of when they are being monitored. They must learn to be monitored in school, we are told, as they can expect to be monitored in their future jobs. Why must schools teach students to accept being monitored? Instead of accepting this premise, would it not be a democratic gesture to prepare students to fight such forms of totalitarianism that are threats to a democratic society in which they, as free human beings, can think, speak and act politically without risk of sanctions or punishments?

6. DIGITAL PICTURES AND THE MESSY REALITY

Today, we can find many examples of how digitalisation is used to make things more understandable by drawing clear pictures of complex matters. However, we must not forget the lack of understanding that accompanies digitalisation. To understand what is said, it is not enough to focus on what is actually being said. The positions from which we speak and the ways in which things are said (e.g. ironically or mirroring contextual norms and values) must always be considered. Unfortunately, such aspects are rarely taken into account when digitalizing things.

Consider, for example, the digital platform Aula introduced in Danish schools in 2019. The purpose of this platform is to collect data about educational matters and to communicate the data to parents and politicians. The data are stored in the Data Warehouse created by the Danish Ministry of Education in 2014. In this digital warehouse, users can shop as customers and find “pre-defined reports and interactive maps, which compare and benchmark schools against municipal and national averages (providing numerical data on, for example, well-being, final exam grades and students’ absenteeism)” (Ratner & Rupert, 2019, p. 8).

The questions are what such data shopping does and what pictures of schools, teachers and students we are ‘sold’ and ‘told’ in the Data Warehouse. They are abstract, numerical imaginative pictures that do not say much about concrete messy reality. That is, what actually goes on in different school contexts. Seeking abstract numerical pictures indicates a paradox as there is a strong (political) focus on concrete educational matters such as whether students follow their individual learning plans, have the right learning attitudes, are willing to learn in the recommended ways and have the sufficient desire to learn. The form of knowledge that seems to matter to politicians is based on monitoring and can be expressed in numerical and data-based ways. Paradoxically, there does not seem to be much interest in other forms of knowledge that might generate more precise insights into the concrete messy educational reality. Many politicians seem to wish to not approach it but instead to be able to inspect and control it from a safe distance. Confronted with the imperfect school realities, for example, we witness a contemporary political tendency to quantify such experiences when qualitative experiences are reported. That is, translate them into numerical pictures. Thus, they seem more orderly and not as horrifying.

Such translation mirrors what is called the Paris syndrome. As Han argues (2017a), this syndrome “refers to an acute psychic disturbance that affects mainly Japanese tourists” who experience fear, anxiety, dizziness and racing hearts when they encounter the “marked difference between the idealized image that travelers have beforehand and the reality of the city, which fail to measure up”. This experience leads to a hysterical “tendency to take photos” which “represents an unconscious defense reaction with the aim of banishing the terrifying truth through images” (Han, 2017a, p. 28). Isn’t it a similar trend that we can see in society in general and in education in particular when more educational matters are translated into “numerical images” to make them easier to handle and enjoy? In mechanical and phantasmatic ways, the problem is that numerical pictures make social antagonisms invisible and, consequently, we lose our sensibility for the dirty, imperfect, complex (educational) reality.

7. CONCLUSION

When we rely on and use digital technologies to produce numerical data and pictures about ourselves, others and (educational) reality, it has consequences in the distribution of the sensible (Rancière, 2004). We must be aware that technologies always divide the sensible, influencing the questions we are (not) encouraged to ask and what is (not) worth spending time on. Many of us use numerical data to inform decision making instead of basing our decisions on democratic discussions. However, if the decisions already favor and are grounded in numerical data that cannot be questioned and problematized there is nothing more to say or discuss. However, big data and digital technologies can inform, enrich and open up for democratic discussions. Especially, if they are used in ways that can transcend our immediate horizons of experience and let us see what we might not were able to see before. And if they are used in ways that support critical thinking instead of controlling and monitoring such forms of thinking in education (Thompsen & Sellar, 2018).

Monitoring by digital technologies takes place not only in totalitarian states but also in democratic western states. In the educational field, digital technologies are used to generate big data, for example, on students’ learning tracks and results. The data can be used to trace “good” and “bad” learning patterns. That is, which patterns must be maintained or broken through regulations, sanctions and punishments. However, is this what education should be about?

If we want to support democratic experiences, conversations and struggles in education and thereby the freedom to think, speak and act in ways not mechanically regulated by numbers, we must question the distribution of the sensible in education (Rüsselbæk Hansen & Phelan, 2019). We must:

challenge the opposition between viewing and acting; when we understand that the self-evident facts that structure the relations between saying, seeing and doing themselves belong to the structure of domination and subjection. It begins when we understand that viewing is also an action that confirms or transforms this distribution of positions. (Rancière 2009, p. 13)

Therefore, it is of vital importance that we avoid, for example, capturing students through digital technologies and reducing them to quantitative forms of data that deny their ontological indeterminacy (Agamben,1993). We should avoid transforming their lives into a “learning game” that supports “willful self-control and reinvention” and makes it difficult to be seen by others as more than numerical data. That is, as special and unique human beings (Lewis, 2013, p. 9).

In addition, we must adopt a strategy that can liberate us from “that which remains captured and separated by means of apparatuses”, in this case, digital technologies (Agamben, 2009, p. 17). By this, I mean that we must try to liberate ourselves from the seductive ideological frames that make us believe (uncritical and without doubt) in instrumental technologies even though we know that they might not support democracy. If we want to support democracy in education we need our freedom to imagine things otherwise (including ourselves and others), our freedom to question things without condition (Larsen, 2019) and our freedom to profane things (to make them inoperative) by releasing them from their normal uses (Agamben, 1993). If we are free to use digital technologies and big data in non-instrumental and mechanical ways and to play with them in new/other ways, we may use them to construct different forms of democratic spaces that we should not be without (Lewis & Alirezabeigi, 2018).

Agamben, G. (1993). The coming community. University of Minnesota Press.

Agamben, G. (2007). Profanations. Zone Books.

Agamben, G. (2009). What is an apparatus? Stanford University Press.

Agamben, G. (2011). Nudities. Stanford University Press.

Agamben, G. (2014). From the state of control to a praxis of destituent power. Void Network, 1–10.

Biesta, G. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: ethics, politics, democracy. Paradigm.

Brown, W. (2015). Undoing the demos: neoliberalism’s stealth revolution. Zone Books.

Clarke, M., & Phelan, A. M. (2017). Teacher education and the political: the power of negative thinking. Routledge.

de la Durantaye, L. (2009). Giorgio Agamben: a critical introduction. Stanford University.

Eynon, R. (2013). The rise of big data: what does it mean for education, technology, and media research? Learning, Media and Technology, 38(3), 237–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.771783

Han, B.-C. (2017a). In the swarm: digital prospects. MIT Press.

Han, B.-C. (2017b). Psychopolitics: neoliberalism and new technologies of power. Verso.

Harvey, D. (2007). Neoliberalism as creative destruction. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 610(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716206296780

Herzogenrath-Amelung, H. (2013). Ideology, critique and surveillance. TripleC, 11(2), 521–534.

Jurgenson, N. (2014, October, 9). View from Nowhere: On the cultural ideology of Big Data. The New Inquiry. https://thenewinquiry.com/view-from-nowhere/

Larsen, S. N. (2019). Imagine the University without condition. Danish Yearbook of Philosophy, 52(1), 42-47.

Lewis, T. (2013). On study: Giorgio Agamben and educational potentiality. Routledge.

Lewis, T., & Alirezabeigi, S. (2018). Studying with the Internet: Giorgio Agamben, education, and new digital technologies. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 37(6), 553–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-018-9614-7

Rose, N. (1999). Powers of freedom: reframing political thought. Cambridge University Press.

Rüsselbæk Hansen, D., & Phelan, A. M. (2019). Taste for democracy: a critique of the mechanical paradigm in education. Research in Education, 103(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523719836671

Rüsselbæk Hansen, D & Toft, H. (2020) Play, Bildung and Democracy: Aesthetic Matters in Education. International Journal of Play (Forthcoming).

Salecl, R. (2010). The tyranny of choice. Profile Books.

Simons, M., & Masschelein, J. (2007). The learning society and governmentality: an introduction. In J. Masschelein, M. Simons, U. Bröckling & L. Pongratz (Eds.), The learning society from the perspective of governmentality. Blackwell.

Sjöholm, C. (2015). Doing aesthetics with Arendt: how to see things. Columbia University Press.

Steinweg, M. (2017). The terror of evidence. MIT Press.

Taubman, P. M. (2009). Teaching by numbers. Deconstructing the discourse of standards and accountability in education. Routledge.

Thompson, G. & Sellar, S. (2018). Datafication, testing events and the outside of thought. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(2), 139-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1444637

Williamson, B. (2017). Big Data in Education: The digital future of learning, policy and practice. SAGE.

Žižek, S. (٢٠٠٨a). The plague of fantasies. Verso.

Žižek, S. (٢٠٠٨b). The sublime object of ideology. Verso.

Žižek, S. (٢٠٠٩a). First as tragedy, then as farce. Verso.

Žižek, S. (٢٠٠٩b). The parallax view. MIT Press.

Žižek, S. (٢٠١٤). Event. Philosophy in transit. Penguin Books.

Žižek, S. (٢٠١٩). Like a thief in broad daylight: power in the era of post-humanity. Penguin Books.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: the fight for the future at the new frontier of power. Profile Books.

Universitat de Vic - Universitat Central de Catalunya (Spain)

Dr. Mar Beneyto-Seoane is an associate professor in the Department of Pedagogy at the Universidad de Vic-UCC. She currently teaches at the master’s degree and the degree of Social Education. Her main fields of study and research are the study of inequalities, inclusion and digital participation in the educational and social areas.

mar.beneyto@uvic.cat

orcid.org/0000-0001-5946-2670

Universitat de Vic - Universitat Central de Catalunya (Spain)

Dr. Jordi Collet-Sabé is a tenured professor of Sociology of Education at the Universidad de Vic-UCC, where he has been the Vice-Chancellor for Research since 2019. He has conducted research and published internationally on educational policies; school, family and community relations; educational equity; family socialization and democracy. He has been Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Education - University College London.

jordi.collet@uvic.cat

orcid.org/ 0000-0001-8526-9997

RECEIVED: January 9, 2020 / ACCEPTED: May 05, 2020

OBRA DIGITAL, 19, September 2020 - January 2021, pp. 29-44, e-ISSN 2014-5039

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25029/od.2020.258.19

Abstract

This article presents the results of a doctoral thesis that analyzes the digital school technology from a democratic perspective and develops an action research to promote the participation, inclusion and reduction of inequalities in this field. The research has focused on thinking, designing and building more democratic digital practices in a diverse Catalan school with the aim of reducing the digital gap that exists between the different members of the educational community and promoting more and better participation and inclusion. In this paper, we show the impact that the incorporation of school digital technology from this democratic perspective generates in the governance of the educational center. Mainly, the results show that this perspective generates more spaces for digital participation and improves the relationships established in these spaces.

Keywords

Social inequality, Democracy, Educational technology, Participation, Family-school relationship.

Resumen

El presente artículo presenta los resultados de una tesis doctoral que analiza la tecnología digital escolar en clave democrática, y desarrolla una investigación-acción para promover la participación, la inclusión y reducir las desigualdades en este ámbito. La investigación se ha centrado en pensar, diseñar y construir prácticas digitales más democráticas en una escuela catalana diversa, con la finalidad de reducir la brecha digital que existe entre los distintos miembros de la comunidad educativa y promover más y mejor participación e inclusión. En este artículo mostramos el impacto que la incorporación de la tecnología digital escolar desde esta perspectiva democrática genera en la gobernanza del centro educativo. Principalmente, los resultados nos muestran que esta perspectiva genera más espacios de participación digital y mejora las relaciones que se establecen en estos espacios.

Palabras clave:

Desigualdad social, Democracia, Tecnología de la educación, Participación, Relación padres-escuela.

Resumo

Este artigo apresenta os resultados de uma tese de doutorado que analisa a tecnologia digital democrática da escola e desenvolve uma pesquisa-ação para promover a participação, a inclusão e reduzir as desigualdades nesse campo. A pesquisa concentrou-se em pensar, projetar e construir práticas digitais mais democráticas em uma escola catalã diversa, com o objetivo de reduzir o fosso digital existente entre os diferentes membros da comunidade educacional e promover mais e melhor participação e inclusão. Neste artigo, mostramos o impacto que a incorporação da tecnologia digital escolar a partir dessa perspectiva democrática gera na governança do centro educacional. Principalmente, os resultados mostram que essa perspectiva gera mais espaços para a participação digital e melhora as relações que se estabelecem nesses espaços.

PALAVRAS-CHAve

Desigualdade social, Democracia, Tecnologia educacional, Participação, Relação pais-escola.

1. INTRODUCtioN

The incorporation of digital technology has shaken the daily practices and dynamics of schools (Bosco et al., 2016). Not only with regard to the material dimension (location of the computer room, the computer cart and interactive whiteboards in the classrooms, among other examples), the time dimension (dedication of a certain amount of teaching time to learning linked to digital technologies) or that related to content (incorporation of digital competence in the school curriculum), but also in what is more hidden and invisible: interpersonal relationships between different educational actors (Albar, 1996; Castells, 2003). Given this situation, a review of the scientific literature shows a persistent and growing interest in the nature (what) and the organization (how) of the relationships that occur in the school context with the use of digital technology. (Adell & Castañeda, 2015; Beneyto-Seoane & Collet-Sabé, 2016; Beneyto-Seoane & Collet-Sabé, 2018; Beneyto-Seoane et al., 2013; Bosco et al., 2016; Cobo, 2017; Fullan, 2013; Selwyn, 2011, 2016). And what are its effects (expected and unexpected) in educational, relational, democratic and inclusive terms.

This article is added to the investigations that seek to describe, understand and improve digital relationships in the educational context from a democratic and inclusive perspective (Baena et al., 2020). Specifically, it focuses on the impact that adopting a democratic perspective in the face of digital school inequalities could generate. For this, it starts from the theoretical framework, methodology and results of a doctoral thesis on democratic digital school technology, in which an action research on participation and digital inequalities in schools is carried out.

2. DIGITAL INEQUALITY AND SCHOOL DEMOCRACY

Talking about digital relationships in the school context implies attending to the relations of digital inequality. But what do we understand by digital inequality in the school context? To conceptualize this term, we start from two references in the field of digital and educational research. On the one hand, the sociological perspective of the Relational System of the Digital Divide (Van Deursen & Van Dijk, 2010; Van Dijk, 2012, 2005; Van Dijk & Van Deursen, 2014). And on the other hand, the Dimensions of School Democracy (Feu et al., 2017; Feu et al., 2016).

Regarding to Relational System of the Digital Divide, Van Dijk (2005) exposes that “the point of departure of this notion of inequality is neither the essences of individuals nor the essences of particular collectives or systems but the bonds, relationships, interactions, and transactions between people” (p.11). In this sense, the relational system is defined as a structure that links different elements that condition, determine or influence digital inequality. For this author, this perspective has two advantages. On the one hand, digital inequality does not reside solely in the particular characteristics of each individual, “this kind of explanation will unearth more of the actual mechanisms creating inequality than will an explanation in terms of individual attributes” (Van Dijk, 2005, p. 12). On the other hand, it allows differentiation of various types of inequality, since it understands that inequality is created according to how the structures of society value and position the individual characteristics of people: “the social recognition of differences and the structural aspects of society refer to the relatively permanent and systemic nature of the differentiation called inequality” (Van Dijk, 2005, p. 12).

The relational system proposed by Van Dijk is characterized by four elements: categorical characteristics (personal: sex, age, birth origin, competencies and personality; and position: work, family, nationality and education); the distribution of resources (power relations with material, temporal, mental, social, and cultural resources); access to digital technologies (related to motivation, material or physical, skills and uses); and participation in society (how people digitally participate in the society). The link established between these four dimensions allows describing how digital inequality is generated and structured:

1.- The structural inequalities of society (derived from the value assigned to categorical characteristics) produce an unequal distribution of resources.

2.- An unequal distribution of resources causes unequal access to digital technologies.

3.- Uneven access to digital technologies also depends on the characteristics of these technologies.

4.- Unequal access to digital technologies causes unequal participation in society.

5.- Unequal participation in society reinforces structural inequalities and unequal distribution of resources.

Faced with this system of inequality, the same author considers that the school environment is one of the most important for applying practices that reduce the digital divide so that it influences the future in the context of society.

In relation to the Dimensions of School Democracy (Feu et al., 2017; Feu et al., 2016), it is a perspective that proposes four dimensions to identify and define democratic school practices. These dimensions are (Feu et al., 2013, pp. 4-6):

- Governance: it refers to the structures and procedures through which political decisions are made and the public is managed; it refers to a method and rules of coexistence.

- Habitability: political participation in freedom and equality not only in a formal but also in a material matter; concern and response to the conditions in which people live; basic conditions of quality of life and well-being for all the people that governance needs.

- Alterity: it is the acknowledgement of those and what is not like “us”, the recognition of the different, the foreigner, the vulnerable person, the minority group, the one who suffers, the one who has another sex or another sexuality or capacity, etc. Also the one that is not human because it is an animal, plant, nature or landscape.

- Ethos: it is defined as a way of being in the world and with others, which constitutes a basic dimension of the previous three […] values and virtues were part of an ethos that manifests itself transversally in all three dimensions.

The reason that leads us to use this perspective of school democracy to analyze digital inequalities is that there is a close link with the relational system approach explained above. A first example of this is that there is a familiarity between the power relation systems (which decide the distribution of resources) and the organs of power (governance). A second example is found in the fact that access to digital technology (whether material or temporary) is directly related to the basic conditions of quality of life (habitability). A last example is that attending to the inequality system implies recognizing the others, who are not like “us” (alterity). In this sense, if we add the relational system of the digital divide approach to the democratic school perspective, we can make visible, analyze and propose responses to the digital inequality that we find in educational centers and among its members (teachers, students, families and administration and services personnel “ASP”). On the one hand, because it contemplates the elements that condition and structure digital inequality (Van Deursen & Van Dijk, 2010; Van Dijk, 2012, 2005; Van Dijk & Van Deursen, 2014). And on the other hand, because it views them from a democratic and inclusive perspective that seeks to overcome these inequalities (Feu et al., 2017, 2013, 2016).

Starting from this double theoretical approach, one of the research questions was: what impacts on inclusion and participation could the incorporation of the democratic digital perspective generate in the school governance of an educational center?

In order to answer this question, we present what were the decision-making processes that were carried out at the center in relation to school organs of government, as well as describe the changes and impacts caused by the digital democratic perspective in the participation bodies (pre and post investigation). We are going to describe this process taking into account the perspective and experience of the different members of the school community: teachers, students, families and administration and services personnel (ASP).

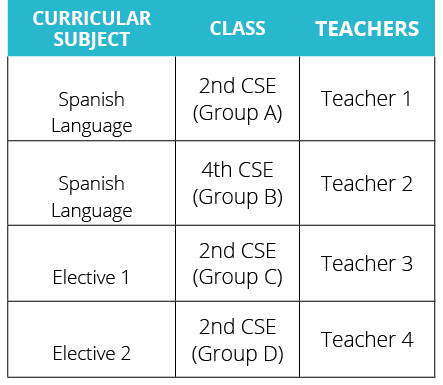

3. METHODOLOGY: RESEARCH ACTION