1. INTRODUCtioN

Globally, digital games have been used for various purposes besides entertainment. An example of this are educational games, whose purpose is to mediate learning, allow the construction of school knowledge and stimulate motor, affective or cognitive skills.

Studies by researchers such as Boyle, Connolly and Hainey (2011) sug-gest that teaching based on digital games can provide effective learning experiences. Authors such as Petry, Contreras Espinosa and Eguia Gómez share the same point of view. Their articles are organized in the book written by Alves and Coutinho (2016) and indicate that research conducted in Europe through focus groups, observations, case studies and content analysis, show that games can effectively contribute to learning.

This is one of the reasons why the digital games industry, especially the Brazilian one, has invested in the production of educational games. The 2nd Brazilian Gamer Census of 2018, ABRAGAMES (2018), showed that the production of these interactive educational environments exceeded the production of commercial games (entertainment). According to the overall census, 874 games were educational and 785 games were for entertainment purposes only, out of the total of 1,718 games produced in Brazil. However, it is important to note that this production is not significantly reflected in the pedagogical practices with games in public and private schools. There have only been occasional experiences such as the Virtual Communities Group, Joy Street productions, among others.

The lack of infrastructure in schools or the quality of games can generate a difficult environment, which may be related to the lack of teacher interaction with educational games. This article aims to discuss how to develop digital educational games that motivate teachers and students, along with the evaluation of what characteristics these games should have.

2. HOW EDUCATIONAL GAMES ARE AND HOW THEY SHOULD BE?

According to Domingues (2018),

…os serious games pretendem que, por meio de sua aplicação, os seus usuários “sintam” um impulso de fazer uma tarefa que de outro modo não estariam tão atraídos em realizar. Ou seja, o que se pretende é que os seus usuários se sintam motivados a executar uma atividade sem grandes dificuldades, algo que os jogos normalmente fazem muito bem. (p. 12)

Despite this perspective, digital educational games do not have to stimulate their players to immerse themselves in narratives, stay motivated and entertain themselves. According to Resnick (2004), entertainment in digital games is a reward after fulfilling missions around school content that need to be learned. That is, the player needs to learn the content before having fun.

As Costa (2009) cites, educational games in general are not fun, while entertainment games have good learning outcomes and are fun. Considering what Costa says, it can be deduced that there is something that does not work with educational games. Perhaps they focus more on content or exercises, when they could learn from games created for entertainment that allow players to experiment joy, entertainment and fun (it emphasizes some exceptions where games such as Assassin's Creed are also being used in school spaces).

For Costa (2009), the development of educational games should be based on the assumption that an educational game must be an entertainment game created from the structure of the knowledge object and not an adapted entertainment game.

This fact was considered by Santos (2014) in the game development process of DOM. According to the author, this game was born from the perspective of articulating the content of quadratic functions with the entertainment and fun features of a game created solely for entertainment purposes. Within an interesting and immersive narrative, the player has direct and indirect access to the content without breaking the dynamics of the adventure.

Despite these experiences, such attractive educational games are not evident in most cases. Most educational games are memory games and other casual games that are often confused with virtualized exercises. In addition, the educational "stamp" presented on the name of the games causes a distance from the students, since their immersion in the school universe is characterized as an obligation and not as a recreational space. In this way, an educational game is related to uninteresting situations for users.

Trying to reverse this stigma, there have been attempts to develop educational games that are closer to the characteristics of entertainment games and that can also directly or indirectly fulfill pedagogical purposes.

To deepen the study, the founding elements present in educational games were characterized by the research detailed in the next section.

3.MATERIALS AND METHODS

To identify how educational digital games are characterized, a review was performed with the literature database (Thomson Reuters, Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC)), the CAPES Thesis Database and the records of the main gaming events from Brazil: The Brazilian Symposium on Games and Digital Entertainment (SBGAMES) and the Seminar on Electronic Games, Education and Communication (SJEEC).

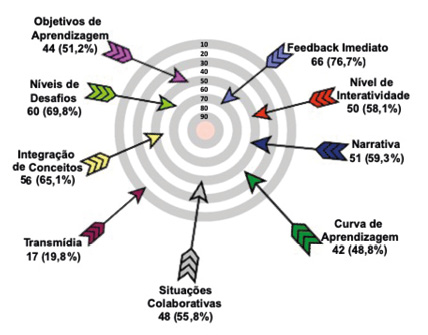

This research conducted in 2018, looked for productions in the Portuguese or English languages with the descriptors of digital games and evaluation produced between 2012 and 2017. When analyzing the productions that evidenced the application of digital games in educational contexts, some elements considered important for digital educational games were identified (it is observed that the emphasis is instrumental, that is, games are present in the school context for a particular purpose: to help learn a concept). The analyzed productions showed the following aspects: immediate and constructive feedback, clear and well-defined educational objectives, challenges in levels, levels of interactivity, concept integration, narrative, transmedia, learning curve and collaborative practices.

After classifying these aspects, an investigation was carried out with a sample of 86 students, professionals and academics from the areas of games and digital technologies. The study was conducted through social networks (Facebook and WhatsApp) and mailing lists (with an online questionnaire available on Google). It was evaluated which of the aspects presented above must be present in a digital game developed for educational purposes.

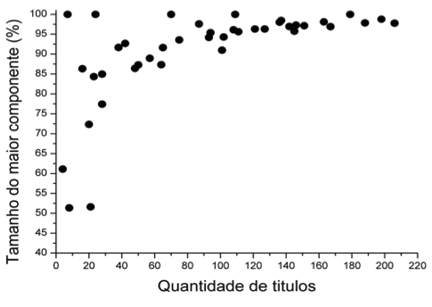

Figure 1. Selected elements

From this survey, it was shown that eight of the nine elements presented similar values. The deleted element (less chosen) was "transmedia". It is considered that research participants cannot yet relate the transmedia extensions that occur for different narratives as an important possibility in the learning scenario. Our hypothesis is that games produced for education are often mini games or casual games that do not start from a narrative that allows the construction and expansion of a transmedia universe, such as games produced by Ubisoft.

The Analytical Hierarchy Process Method – AHP, is a decision making technique that establishes the relative importance between several criteria, comparing and placing them in a general classification of alternatives. This was the method that was used to establish the level of importance of each of the elements indicated above.

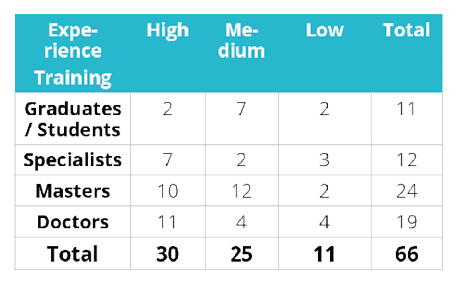

In this stage, 66 responses were obtained and the subjects involved in the research were classified according to their training and their level of experience in digital games, as can be seen in Table 01.

Table 1. Training and Experience

According to the training of the participants, this division allowed to establish relations between the educational level and the generational stages in which they were, paying attention to their level of experience or knowledge in the area of digital games.

4. RESULTS

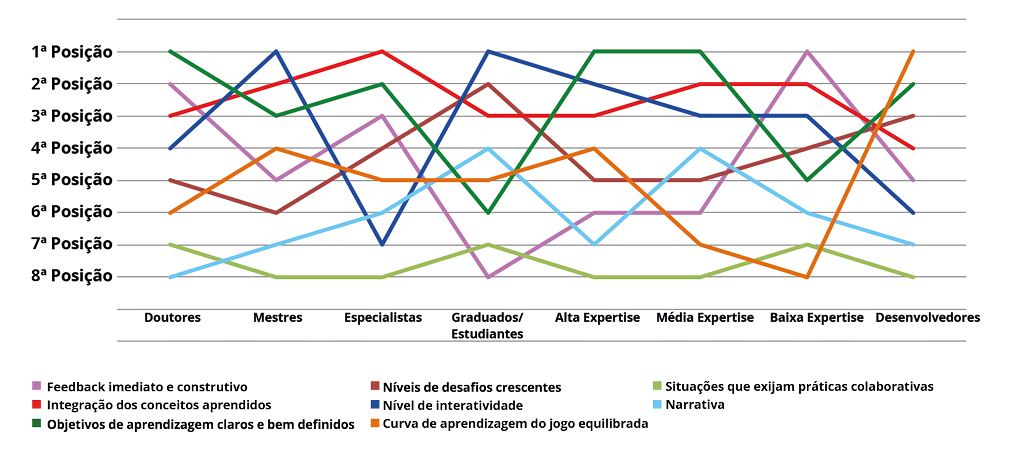

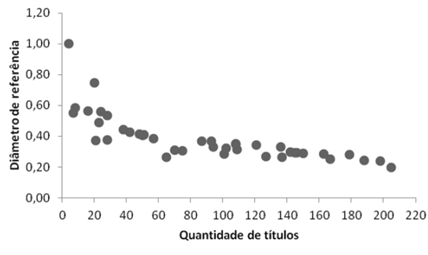

After applying the AHP Method, the elements could be compared within the level of importance recorded from their positions, as can be seen in Figure 2.

Analyzing these data based on the training of the participants, it can be evidenced that the graduates/students think that digital educational games must prioritize the levels of interactivity, increase the levels of challenge and the integration of concepts. In order to identify the motivators of this selection, it must be remembered that the graduates/students were part of Generación Z which, according to McGonigal (2011), is composed of young people with an average of 21 years of age who have spent over ten thousand hours with digital games and have invested only three thousand hours reading books in their life.

The integration of concepts, objectives of learning and feedback were the aspects of the composition of digital educational games that drew the attention of people with more specialization. For those with a master’s degree, the most important elements are interactivity, integration of concepts and learning objectives. For those who have completed a doctorate, priority is given to learning objectives, feedback and concept integration.

As a result of observing these four profiles, the learning objectives stand out as one of the three elements that experts and people with fourth level education consider most important for digital educational games. Here appears the first disagreement on the conception of digital educational games. Expectations for students/graduates are different from those who intend to use these resources with educational purposes, that is, their teachers. Taking into account that most of them are consumers of digital games for entertainment.

Figure 2. Comparative Chart

Here are the main problems in the development of digital games for school learning scenarios: neglecting entertainment and forgetting that games have to be fun. This is what the study seeks to find, the idea that it is possible to have fun and learn, as is evidenced in Minecraft.

In the conception of teachers, the resources used in the school must seek the learning of contents. This criterion becomes a priority. As quoted by Pretto (2013), teachers have an instrumental perspective of technologies, but they consider them as simple animators of classes without building a view that can identify them as elements that enhance pedagogical prac-tices. Therefore, when thinking about digital games as animated electronic books, basic characteristics of these artifacts are neglected: entertain or allow to distance from real life, for example (Huizinga, 2000).

This dichotomy of views has sparked a discussion about entertainment and educational games, which are not so fun. For this reason, students and players are not interested in interacting with this type of game.

An issue that is shown in the comparative graph (figure 02) is the low score in "situations that require collaborative practice". In spite of the fact that collaboration could be one of the important factors for success in multiplayer games, this potential for educational games is not perceived. This is a major contradiction, considering that educational practices must prioritize collaboration and cooperation over competition and individual learning.

A possible reason for this is that the skills related to social interaction and collaboration in problem solving are not always evident in schools. Usually, the students think that group work has to be done individually to be later integrated; they do their part instead of looking for collaborative work. Therefore, these skills are also not considered for digital games. This information is based on the experience of the authors of this article, who have been working on basic and higher education during more than twenty years.

Another point that can be observed is the place occupied by the narrative for interviewees who are farther from the students. For graduates/students, the narrative is an element of intermediate importance, while it is the penultimate item for people with fourth level education. According to Alves, Martins and Neves (2009):

[...] One of the factors that attracts more players to the narratives offered by the games is the possibility of choosing a path that often goes beyond the common linear logic of conventional narrative formats. Another important factor is that the narrative of games is not simply understood and interpreted by the players, but experienced and defined through the transformation of players into characters. (p.10)

For this reason, the narrative is an important element for the player to be transported to the fictional world of the game and have a greater immersive experience. This fact is also evidenced by game developers who have invested heavily in digital game narratives, as noted in the Assassin's Creed and God of War games. On the other hand, educational games have not yet presented good narratives, becoming boring games that do not attract. They often become virtualized exercises without a context or story that connects them to the logic of the game. Usually, "mini games" have no relation to the main theme of the game. However, the opening of courses and book publications that discuss the participation of the narrative in education is emphasized at the market level. The culture is marked by narratives that seduce, involve and motivate humans.

A similar behavior was found with the “increasing challenge of levels” item whose importance decreased with the increase in the level of education. It is common for players that the challenges grow at each stage of the game, since the player needs to establish new strategies using previously acquired knowledge for each new challenge in order to win.

One of the most important points in the games is the conflict because each player seeks appropriate challenges, thereby solving the problem of game balance. This is why mechanisms must be created to adequately challenge the player, avoiding boring him with trivial tasks or frustrating him with impossible tasks. (Andrade et al., 2005, p.13)

For this reason, authors such as Gee (2005) point out that the school needs to learn from game designers how to propose a balance in activities and challenges for students, offering rewards and learning compatible with their experiences in the game. Therefore, paying attention to the learning curve present in the "gameplay" is essential.

Analyzing the obtained data and taking into account the level of experience of the subjects, it is observed that the responses of those who consider themselves with little experience in the field of digital games, the three most important elements were: feedback, integration of concepts and “interactivity”. For those who consider themselves of medium expertise, the three priorities were "clear and well defined learning objectives", "integration of concepts learned " and "level of interactivity".

A similar event occurred with those who consider themselves very skilled in digital games, who maintained these same elements as priorities. However, "clear and well defined learning objectives" remained first, "level of interactivity" ranked second and "integration of concepts learned" ranked third.

Analyzing the comparative chart (Figure 02), it was possible to identify that the integration of concepts learned is an element that remains in the first positions, regardless of the level of experience. This highlights the importance of the application of concepts and their feedback in a digital educational game.

This fact is corroborated in the discourse of Botelho (2004) when he states that:

digital games can be used for operational skills training, awareness and motivation reinforcement, knowledge and perception development, communication and cooperation training, integration and practical application of the concepts learned, and even the evaluation. (p.12)

The level of interactivity is also among the most important elements. According to Prensky (2012), interactivity is present in digital games through practice and feedback. That is, the player learns through tests and errors. The player must be free to act guided by objectives, discover-ies, tasks and questions in order to have a better immersion in the activity.

There is also an increase in the importance of the item “clear and well defined learning objectives” for those with a higher level of expertise, which shows the concern that educational games need to define this item well as a way to better mediate learning.

Corroborating this thought, Lemos (2016) indicates that:

To be used for educational purposes, games must have well defined learning objectives, teach the content of the subjects or promote the development of important strategies or skills to increase the cognitive and intellectual capacity of students. (p. 11)

According to the author, it is possible to note that she relates the learning objectives to content teaching. Which indicates that if the game aims to teach certain content, there is a need to define learning objectives. On the other hand, if the game seeks to promote the development of other skills, defining them would not be necessary.

A controversial element in the comparisons was the feedback, which decreased in importance as the level of experience increased. This fact is contrary to the perspective of authors such as Rhodes et al. (2017), Freitas Araújo and Almondes (2015), Tonéis (2015), Sung, Chang and Liu (2016), who defend the importance of this element as one of the main items to be considered in educational digital games.

Looking at the perspective of the developers, it can be seen that digital games for educational purposes should include a "balanced learning curve", followed by "clear and well defined learning objects" and "increasing challenge of levels." Considering these data, it is important to keep in mind that, as developers, these professionals seek to produce a game whose design attracts their consumers and provides a better immersion and flow experience. Attention to the learning curve is key for this to happen, as it motivates players to interact continuously and maintains their persistence and tolerance towards "mistakes" and losses.

According to Trois and Silva (2012), a game must have a well balanced learning curve. If it is very flat, active perception, fun and learning are less intense. If the curve is too high, it will make the player find the game difficult and lose interest in it.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Digital Game Based Learning (DGBL) is gaining importance on the world stage as the production of these technologies increases.

The data presented confirm the premise that games for educational purposes are not fun like entertainment games (commercial games). The latter, ironically, end up being more effective than educational games when used for pedagogical purposes.

Through the analysis of the data presented in this research, it was observed that the generational differences impact on the understanding of how a digital educational game should be. Students, people with third and fourth level education and developers understand digital educational games from completely different points of view and this has a strong impact on the final product that is developed and used in schools.

What most interests players is to immerse themselves in the fictional environment created by digital games and for this reason they prefer interactivity and challenges. People with more training, masters or doctorates, often focus on preparation through continuous evaluations and seek to address the integration of concepts and learning objectives.

Taking these results into account, it becomes increasingly necessary to discuss the participation of entertainment games in education, the differences between them and the games produced for educational purposes. The best way is to listen to students and learn about their experiences and interests around the digital universe and, especially, digital games. In this way, games can be produced in tune with the desires and interests of the users, but considering the school concepts that must be presented and stimulated. At the same time, the specificity of digital games as a product and as a language with its limits and possibilities must be respected.

We believe that the findings and confirmations of previous studies evidenced in this article can support the development of new digital educational games and support what teachers and game designers should consider in the production of these media in order to make them more effective in school learning.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ABRAGAMES - Associação Brasileira das Empresas Desenvolvedoras de Jogos Digitais. (2018). Dados sobre o Mercado de Games do Brasil. Retrieved from: http://www.abragames.org/o-que-estamos-fazendo

Alves, L., and Coutinho, I. (2016). Games e educação: Nas trilhas da avaliação baseada em evidências. In: Alves, L., Coutinho, I. (Org.). Jogos digitais e aprendizagem: Fundamentos para uma prática baseada em evidências (pp. 9–15). Campinas-SP: Papirus.

Alves, L., Martins, J., and Neves, I. (2009). A crescente presença da narrativa nos jogos eletrônicos. In: VIII Brazilian Symposium on Games and Digital Entertainment. PUC. Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: [s.n.]. Retrieved from: http://www.sbgames.org/papers/sbgames09/culture/full/cult2_09.pdf

Andrade, G., Ramalho, G., Santana H., and Corruble, V. (2005). Challenge-sensitive action selection: an application to game balancing. In: IEEE. Intelligent agent technology, ieee/wic/acm international conference (pp. 194–200). France: Compiegne. Retrieved from: http://repositorio.roca.utfpr.edu.br/jspui/bitstream/1/8329/1/PG_COCIC_2017_2_09.pdf

Boyle, E., Connolly, T. M., and Hainey, T. (2011). The role of psychology in understanding the impact of computer games. Entertainment Computing, 2(2), 69–74. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1875952110000200

Botelho, L. (2004). Jogos educacionais aplicados ao e-learning. São Paulo. Retrieved from http://www.elearningbrasil.com.br/news/artigos/artigo\_48.asp

Costa, L. D. (2009). O que os jogos de entretenimento têm que os jogos educativos não têm. In VIII Brazilian Symposium on Games and Digital Entertainment: 8-10 de outubro de 2009 (pp. 8-10). Rio de Janeiro.

Domingues, D. (2018). O sentido da Gamificação. In: Gamificação em debate / Organização de Lucia Santaella, Sérgio Nesteriuk, Fabricio Fava. – São Paulo: Blucher.

Freitas-Araújo, D. de, and Almondes, K. M. de. (2015). Evaluation of intervention with electronic games upon cognitive processes of elementary school students in a Brazilian state-run school: the role of sleep. Biological rhythm research, 46(3), 389 – 401. doi:10.1080/09291016.2015.1015234

Gee, P. (2005). Learning by design: Good video games as learning machines. E-Learning and Digital Media, 2(1), 5–16. doi:10.2304/elea.2005.2.1.5

Huizinga, J. (2000). Homo ludens. Trad. João Paulo Monteiro.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York: NYU press. Retrieved from: https://www.hse.ru/data/2016/03/15/1127638366/Henry%20Jenkins%20Convergence%20culture%20where%20old %20and%20new%20media%20collide%20%202006.pdf

Lemos, R. da F. (2016). O uso dos jogos digitais como atividades didáticas no 2° ano do ensino fundamental. 26 f. Monografia Especialização — Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Retrieved from: https://repositorio.ufsc.br/bitstream/handle/123456789/168860/TCC_Lemos.pdf?squence=1&isAllowed=y

McGonigal, J. (2011). Reality is broken: Why games make us better and how they can change the world. New York: Penguin.

Prensky, M. (2012). Aprendizagem baseada em jogos digitais. SENAC, São Paulo, p. 575.

Pretto, N. de L. (2013). Uma escola com/sem futuro: Educação e multimídia. EDUFBA, Salvador.

Resnick, M. (2004). Edutainment? No thanks. I prefer playful learning. Associazione Civita Report on Edutainment, MIT Media Laboratory, 14, 1-4.

Rhodes, R. E. et al. (2017) Teaching decision making with serious games: An independent evaluation. Games and Culture, 12(3), 233–251. doi:10.1177/1555412016686642

Santos, W. S. (2014). DOM: um modelo de game para a aprendizagem das funções quadráticas no ensino médio. Dissertação. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Modelagem Computacional e Tecnologia Industrial - Centro Universitário Senai Cimatec, Salvador/BA.

Santos, W. S. (2018). PAJED: um modelo de avaliação para jogos digitais educacionais. Retrieved from: https://12c3b48d-162b-3b3a-fc8a-2606b9d4af6e.filesusr.com/ugd/5d4133_778e405012704102b37c134417d2ca81.pdf

Sung, Y-T., Chang, K-E., and Liu, T-C. (2016). The effects of integrating mobile devices with teaching and learning on students’ learning performance: A meta- analysis and research synthesis. Computers & Education, 94, 252–275. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131515300804

Tonéis, C. N. (2015). A Experiência Matemática no Universo dos Jogos Digitais: O processo do jogar e o raciocínio lógico e matemático. 160 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Matemática) — Universidade Anhanguera de São Paulo–UNIAN/SP, São Paulo. Retrieved from: https://www.capes.gov.br/images/stories/download/pct/2016/Teses-Premiadas/Ensino-Cristiano-Natal-Toneis.PDF

Trois, S., and Silva, R.P. da (2012). Desafiando para ensinar: estudo comparativo entre níveis de dificuldade em games educacional e comercial. In: Brazilian Symposium on Computer Games and Digital Entertainment, XIX. (pp. 93–99). Brasília: Sbgames. Retrieved from http://sbgames.org/sbgames2012/proceedings/papers/artedesign/AD_Full12.pdf

1. GLOBALIZATION AND ORAL TRADITIONS: SOME REMARKS ON INDIGENOUS ORALITY IN THE AMAZON

Among the native ethnic groups that live in the Ecuadorian Amazon regions, orality keeps representing an important element that plays an irreplaceable role in the daily life of their members.

Thanks to the efforts of researchers, anthropologists, ethnographers and linguists who publish their works that comprise all genres of authentic indigenous oral traditions, there is a guaranteed and a reliable access to a wide range of plausible examples of living oral expressions and traditions that document the immense cultural diversity in the Amazon. This effort is not only important because of the results motivated by proper research objectives, but it is also very valuable seen from other, more general, perspectives related to the current situations in indigenous communities from the Amazonian regions.

As numerous recent surveys and researches show, there is a great number of indigenous languages that are in danger of extinction (Stewart, 2019), it is symptomatic that many of them are from Latin America. The alarming situation is quite obvious if we consult the Atlas of Endangered languages (UNESCO, 2017). Languages that are spoken in different parts of the world and find themselves in danger of extinction, are traced on interactive maps with all sort of relevant data. The explicatory notes include a division of those languages into six fundamental categories. The first one is defined as a safe status, while the last one is the category reserved for extinct languages. This division characterizes the safety of a language based on particular criteria: those languages that are considered endangered are divided according to the extent of the danger, which corresponds to a five-degree scale. Each degree is differentiated with one symbolic color. The first degree of danger is related to a white color and it comprises the category denominated Vulnerable. It is followed by the category of Definitely endangered languages, which is represented by a yellow color. The next degree is called Severely endangered and its color is orange. The following degree includes Critically endangered languages and is marked in red, as can be expected. The last category lists extinct languages, and that is why its color is black (ibid).

While looking at the map that documents the situation in Ecuador, we can assume that the current state is quite worrying. The registered results speak for themselves. One language is categorized as vulnerable. It is the case of Waotededo, whose speakers live in the heart of the Amazonian region. There are two cases of critically endangered languages. The first of them is Zaparo and is spoken by communities in the North of the country. The second is Sia Pedee, whose speakers live in the areas located deep in the West of the Ecuadorian Amazon region, close to the Peruvian border.

Five languages are recorded as critically endangered. Some of them are linked to communities that live in the Amazon region, as is the case of Awapit, Siona/Secoya or Shiwiar. These can serve as examples to illustrate the alarming situation related to critically endangered indigenous languages spoken on the territory of the above mentioned South American country (UNESCO, 2017). The majority of languages presented in the map are considered to be severely endangered. To be more specific, there are nine of such cases. As typical examples can be mentioned three of those languages: A´ingae/Cofan, Achuar and Shuar chicham (ibid).

In this context, it is crucial to point out the important role of Universities that try by all means to prevent the extinction of endangered languages. University academics and researchers, mainly from the Humanities fields, often combine specific research goals of projects with the struggle for conservation and preservation of indigenous languages. It is common that a language can be registered in the category with a safe status only if it is spoken by all members in the community which it is linked to, and by the youngest generations. It is not a coincidence that the criteria for considering a language as critically endangered are based on the fact that: “the youngest speakers are grandparents and older, and they speak the language partially and infrequently.” (UNESCO ATLAS, 2017). As Victoria Tauli-Corpuz points out “Safeguarding living heritage is very crucial for indigenous peoples because their heritage is the basis of their identity, the basis of their cultures and, of course, it is the continuous transmission of this heritage that is going to strengthen indigenous peoples’ identities and cultures” (UNESCO, ICH, 2019, p. 2).

An inherent part of the indigenous cultural heritage is represented by the diverse oral traditions that constitute one of the basic pillars of the social life in many Amerindian communities in Ecuador. The academia is aware of the dangers that jeopardize the future of the vulnerable indigenous languages, that is why there is an increasing number of projects that aim to prevent the extinction of endangered languages. The University of Azuay can be mentioned as an example worthy of imitation. From among all the university projects related to the indigenous culture, there are some focused precisely on indigenous oral expressions and traditions, where UDA professors and their students have collected examples of living oral tradition. One of such projects worth mentioning has been carried out under the supervision of Narcisa Ullauri (Torres Jara, G., Ullauri, N., and Llangui, J, 2018), senior professor who is engaged in the issues of indigenous cultural heritage. Among the outputs of this project, we can find collections of Shuar oral tradition that inspire students to pay attention to the Shuar community when preparing their thesis or academic projects.

There is another important fact that needs to be pointed out. If such collections are published, they constitute an important source of authentic material that can be studied from different perspectives and diverse disciplines. Moreover, if they are available in Spanish or English translations, the circle of potential researchers or just readers can grow. Thanks to the meticulous effort of those who take an active part in such projects, there is a plausible source with authentic study material for all those who wish to get familiarized with the particular samples of the cultural legacy of the Amerindian peoples from the Ecuadorian Amazon.

According to Carneiro da Cunha:

There is always a double dimension in culture. One is what could be termed an internal dimension, that is its living practice, the practice of its producers and is related to its creativity. Then there is something like an external but equally fundamental dimension, which has to do with the assertion of identity of a group vis à vis other groups. (2001)

The indigenous oral traditions are important in the life of Amerindian communities not only because of its cultural dimension and identity significance, but also due to its agglutinating role in the life of the community. In this connection it should not be forgotten that the great variety of particular manifestations of indigenous orality represent an element that plays an important role in the life of the community, since the oral expressions are performed mostly as collective acts. This fact is crucial because the public performance contributes to underlining the important identity components of the community. Moreover, it is frequently repeated in order to strengthen the ties among its members. In this sense, the oral tradition not only represents the core of the indigenous culture, but a key factor with relevant social importance.

The importance attributed to the identity as one of the crucial elements in indigenous communities is also underlined in the definition of the concept of the intangible cultural heritage provided by UNESCO, where it is presented as a kind of ‘living heritage’ and as such it is considered “important because it offers communities and individuals a sense of identity and continuity. It can promote social cohesion, respect for cultural diversity and human creativity, as well as help communities and individuals to connect with each other.” (UNESCO, ICH, 2019).

Amerindian communities from the Amazon keep their ancestral cultural heritage alive by passing it conscientiously from one generation to another. For long centuries, they have tried to conserve their knowledge in oral traditions and performances that, along with their ceremonies, rites and rituals, constitute the base of their intangible cultural heritage.

Thanks to various external factors over the past two decades, awareness and recognition of indigenous cultures in Latin America has grown slightly. This fact has contributed to an increasing appreciation of indigenous languages. Their presence at a national level is being more visible in comparison with the situation 30 years ago, due to their changing role in the society. Though the situation is far from being ideal, nowadays at schools and colleges of all education levels, from elementary schools to universities, students can get in touch with indigenous languages more frequently. It is due to the fact that in many Latin American countries there is a progressive tendency to enhance the integration processes concerning the use of indigenous languages. Therefore, they cease to be only objects of study and become representations of instructional languages. As Fajardo Salinas (2011) presents it, the notion of interculturality emerges in this context thanks to changes in the way of understanding the cultural diversity. This includes situations when indigenous languages pass from being considered a problem to being looked upon as a resource, which is complemented by the bilingualism of maintenance and development, with the proposal of a dialogic relationship between the two languages and two cultures they represent.

There is one more important aspect that should be mentioned when speaking about the possible concepts of the orality. Some scholars define orality as a pattern that:

describes cultures or populations whose worldviews, rhetorical principles, and mental constructs develop in the absence of widespread, systematic, and habitual literacy and also refers to the coexistent or residual presence of orality in habitually literate cultures. Therefore, it is necessary to distinguish between primary orality and secondary orality. Primary orality (and thus primary oral cultures) describes cultures that privilege the spoken word as the only means of social and interpersonal communication, often lacking even a basic orthography. Secondary orality describes the presence of oral and/or pseudo-oral elements in habitually literate cultures. (Jacobsen, 2007)

In relation to the distinction of primary and secondary orality defined by Walter Ong (1996), Daniel Murillo observes an essential paradox which is related to the primary orality. On one hand, it allows memory to be activated and permits consultation of what he calls corpuses; i.e. the set of knowledge, habits, traditions, representations, symbolisms, meanings and language in a given social group (Murillo, 1999). As the author points out, it makes possible the query to an unwritten, but permanent file. On the other hand, once the words leave the mouth and are said, they also cease to exist in their acoustic form as sounds, even if the range of possibilities towards the meaning is opened. Orality is, according to Murillo, transience and permanence (ibid). It is the conjunction between the immediate and the mediate, between ancestral memory and non-memory. This double phenomenon has allowed orality to debate between the world of written culture and transform. Oral cultures exist because they have a common history, common values, a corpus and a culture; but the so-called written cultures would seem to suffer from it. It is believed that by being in books, traditions are not lost, memory is not fleeting and the corpus can be fed in different ways (Murillo, 1999).

As Juan Goytisolo (2001) states, when speaking about the antiquity of the oral heritage of Humankind, it is equally significant to pay attention to several factors that help us understand the interaction between oral traditions, written expressions and the growing imbalance that characterizes it. According to the Spanish author, only seventy-eight languages out of the three thousand languages spoken today in the world, have a living literature founded on one of the one hundred and six alphabets created throughout history. In other words, Goytisolo (2001) points out the fact that there are hundreds of languages currently used on our planet which lack writing. Consequently, the communication of their speakers is exclusively oral (Goytisolo, 2001).

Due to the impact of different factors in the contemporary globalized world, the indigenous orality is subject to permanent changes that leave a considerable mark. As a consequence, the traditional ways of oral expression pass through a process of smaller or bigger changes. Margarita Zires refers to the observations of Paul Zumthor (1987) about the tradition that is understood as an open series, indefinitely extensive in space and time, of the variable manifestations of a particular archetype. But this archetype is not conceived as a static model, since it designates a set of pre-existing virtualities that precede all textual production (cfr. Zumthor in Zires, 1999).

In this context, Gabriel Poratti (2010, pp. 99-100) points out to another effect of globalization that is reflected in the fluid cultural exchange. This process is greatly enhanced by the advent of new communication technologies, such as telephone, TV or Internet. As Poratti perceives it, the main contributions of the Internet are represented by the facts that different forms of communication have accelerated. One of the most significant consequences of such speed has been reflected in the feeling that the world has become smaller and we have reached the point where information or people are found at a simple “click” away. (Poratti, 2010, p.100)

In the long history of the humankind, there were many historical eras when the society was exposed to various radical changes. Nevertheless, none can be compared with this period in which we live with regard to the extent, depth and impacts of such changes.

“Like other forms of intangible cultural heritage, oral traditions are threatened by rapid urbanization, large-scale migration, industrialization and environmental change. Books, newspapers, magazines, radio, television and the Internet can have an especially damaging effect on oral traditions and expressions. Modern mass media may significantly alter or replace traditional forms of oral expression.” (UCH, 2006)

In relation with various impacts on the oral traditions, there is another aspect worth mentioning. As Juan Goytisolo (2001) states, all cultures are based on the language, that is, on a set of spoken and heard sounds. This oral communication, which also includes numerous kinesthetic or physical elements, has experienced a series of changes over the centuries. These modifications depend on the extent of contacts with other forms of communication, transmitted at the beginning due to the existence of the writing. Knowledge of writing has gradually influenced the mentality of the rhapsody or the narrator. According to the Spanish writer, it is difficult to find depositories of an oral tradition absolutely “uncontaminated” by writing and its technological and visual support in today’s world of mass media. (Goytisolo, 2001)

In the struggle for the conservation of indigenous orality as an inherent part of the intangible cultural heritage of the Amerindian people, it is vital to promote indigenous culture and encourage native speakers to use their languages actively in everyday situations. The natural and frequent use of vulnerable indigenous languages spoken by all generations in a particular community is the only effective prevention of the danger of their extinction. In this uneasy process, the academia can contribute with its own means. On one hand by encouraging the native speakers to use their language and on the other hand by making the indigenous cultural heritage accessible to the majority of society. This is the first step that can help to increase the respect and appreciation for indigenous languages and cultures.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carneiro da Cunha, M. (2001). Notions of Intangible Cultural Heritage: towards a UNESCO working definition. UNESCO.ORG. Retrieved January 6 2020 from: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/05357-EN.pdf

Fajardo Salinas, D. M. (2011). Educación intercultural bilingüe en Latinoamérica: un breve estado de la cuestión. LiminaR 9(2), 15-29. San Cristóbal de las Casas dic. 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2020 from: http://bit.ly/2sgEIGF

Goytisolo J. (2001). Escritura y Oralidad. International Round Table.UNESCO.ORG. Retrieved from: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/05360-ES.pdf

Jacobsen, M. M. (2007). Orality. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/2ThKeUl

Murillo, D. (1999). Especie de prefacio a comunicación y oralidad. Razón y palabra, 4, 15. Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/35ISY8F

Poratti, G. G. (2010). El shock del siglo XXI. ¿Por qué el mundo va hacia una crisis? ¿Cómo haremos para salir de ella? Buenos Aires, Editorial Red Universitaria.

Stewart, K. (2019). Indigenous Languages Are in Danger of Going Extinct. World Politics Review. Retrieved January 6, 2020 from: http://bit.ly/35HzVeY

Torres Jara, G., Ullauri, N., and Llangui, J. (2018) Las celebraciones andinas y fiestas populares como identidad ancestral del Ecuador. Universidad y sociedad, 10(2), 294-303.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, (UNESCO, 2017). Atlas of Endangered languages. UNESCO.ORG. Retrieved January 6 2020 from: http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Intangible Cultural Heritage (UNESCO, ICH, 2019). Living Heritage and Indigenous Peoples. the convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. UNESCO.ORG. Retrieved January 6 2020 from: http://bit.ly/36YMwvy

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH,2006). Oral traditions and expressions including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage. UNESCO.ORG. Retrieved January 6 2020 from: https://ich.unesco.org/en/oral-traditions-and-expressions-00053

Zires, M. (1999). De la voz, la letra y los signos audiovisuales en la tradición oral contemporánea en América Latina: algunas consideraciones sobre la dimensión significante de la comunicación oral. Razón y palabra 4(5). Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/30kAY3p

1. INTRODUCtioN

In recent decades, it is possible to affirm that research in the area of communication has experienced high growth (Fernández-Quijada and Masip, 2013), especially if it is compared with other disciplines belonging to the field of social and human sciences. This development has taken place in parallel with that of the “network society” (Castells, 2006), increasingly conditioned by the “Internet galaxy” (Castells, 2001) and by the use of the Information and Communication Technologies – hereinafter, ICT – that have become the leading agents of the 21st century. In the opinion of Marinho and Vicente-Mariño (2018), the continuous and accelerated social and technological transformations have moved communication studies to a prominent place in the scientific aspect worldwide.

Another reason that motivates this circumstance lies in its interdisciplinary nature, resulting from a permanent intersection and feedback with other academic disciplines such as anthropology, economic sciences, political sciences, psychology or sociology (Pfau, 2008). In addition to highlighting its intrinsic interdisciplinary nature, it is analyzed by experts both from the perspective of integration (Wallerstein, 2005; de-la-Peza, 2013) and fragmentation (Craig, 2008; Calhoun, 2011). It is necessary to underline another very attractive characteristic that studies in this area bring together: their particular multidisciplinarity, since the potential they exhibit to be articulated with other epistemological domains is practically unlimited.

If it is true that this double nature - interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary - helps to understand the importance that scientific literature in communication has acquired, it also allows us to notice the many challenges it faces, since it can and should contribute both to the analysis and to the understanding and reflection of some of the central issues of today's society. It is in this complex scenario where this initiative is located, whose main purpose is to observe what space it occupies and how the fields of culture, heritage and tourism are addressed in the articles published in the main communication journals at the Hispanic level.

1.1 STATE OF THE ART

Although the number of studies where the association between these three fields and communication has increased, we cannot ignore the fact that this approach is, as a general rule, recent and of uneven origin. Before continuing with this brief review of the state of the art, it is clear that we do not consider delving into an exhaustive characterization of its domains. However, it is necessary to clarify that, as far as culture is concerned, it is conceived as “a set of ideas – values, attitudes, and beliefs –, practices – of cultural production – and artifacts – cultural products, texts –” (Hanitzsch, 2007, p. 369). In this context, the notion of culture has always been closer to communicative research, especially if we consider a specific sense of the term: one that explores the creation, dissemination and interpretation of messages with certain cultural meanings.

Both heritage and tourism are closely related to each other and represent newer niches for informational studies. Probably, the pioneers in watching the encounter between communication and tourism were Boyer and Viallon (1994), who pointed out the multiple labels that the tourist phenomenon presented at that time at the multidisciplinary level; among them: “idle behavior” from psychology, “consumerism” from economics, “elitism” from anthropology or sociology, “evolution of post-industrial society” from history, or “migratory phenomenon” from geography. Along these same lines, Marujo (2012) affirms that the complexity of tourism from a cultural, economic, political and social point of view exceeds the borders of a single field of knowledge, highlighting the need to deepen its communicational aspect.

It is convenient to emphasize that when we refer to any of these realities, we are referring to complex and multidimensional concepts, that is, "constructs". Regarding tourism, Osorio (2016) recalls that “types of tourism respond to different and diverse activities with respect to relationships with the environment and people (...) This makes approaching tourism as a discipline requires different methodological and theoretical tools” (p. 288). As for heritage, it allows us to discuss the links between the past and the present, providing us with historical depth in a changing world (Bessière, 1998). At the typological level, “it can be natural - relating to an environmental ecosystem -, or cultural - pertaining to the social and human context -, and cultural heritage in turn can be tangible or intangible” (Piñeiro-Naval, Igartua and Rodríguez-de-Dios, 2018, p. 2).

This heterogeneous dimension of the notions of culture, heritage and tourism contributed to the development of academic initiatives where all three are connected. As Marujo (2015) argues, during the 1990s there was a great emergence in the observation of synergies and dysfunctions between them. This current of research materialized in the creation of specialized scientific journals, which generated “a wide bibliographic production that includes epistemological analyzes, case studies, theoretical approaches and a great critical mass that provide the basis for initiating a scientific dialogue on the relationship between tourism, culture and nature” (Osorio, 2016, p. 286).

Together, these academic coordinates allow us to warn the emergence and profusion of multiple scientific documents that deal with the interrelation between culture, heritage and tourism in the current information society. As Carvalho (2018) expresses, "the advent of new information and communication technologies expanded not only interest, mediation and dissemination of heritage, but also boosted the growth and transformation of tourism activity" (p. 28) and, we might add, cultural.

2. OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY

Academic production on a subject is considered to act as a reliable symptom of the attractiveness it generates in the scientific community (Pérez-Montoro, 2016). Consequently, the goal of this project was to document the research related to the fields of culture, heritage and tourism, published during the 2013-2017 period in the main Hispanic communication journals. Based on the main purpose, the following specific objectives were raised:

- O1: describe the production from the bibliometric point of view.

- O2: iidentify the elements that organize this work at a theoretical and methodological level.

- O3: compare the fields of Spanish and Latin American publication.

Two techniques such as bibliometry and meta-research were combined, "a quantitative descriptive method linked to the techniques of content analysis, specially designed to investigate how the “format” of a scientific article is organized as a means of communication and dissemination among specialized audiences” (Saperas and Carrasco-Campos, 2019, p. 222). This methodological triangulation (Denzin, 2012, 2015) allowed addressing aspects such as authorship or financing of articles – bibliometric items – and identifying the objects of study, theories or methodologies used in the publications of the sample. With what criteria was this sample designed? It was designed according to a multi-stage plan (Neuendorf, 2016) organized in different phases.

Initially, Spanish and Latin American journals with the highest impact index in 2017 were selected, these were present in the international database of Scimago Journal & Country Rank in the communication category. It was stipulated that the journals had to appear in the first two quartiles to be considered of impact, which generated a total of 7 headers: Comunicar, El Profesional de la Información, Communication & Society, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, Cuadernos.info, Comunicación y Sociedad and, finally, Palabra Clave. Likewise, a five-year period was reversed until 2013 to make a cross-section with a certain chronological perspective.

Once the journals that acted as data collection units were identified, the next step consisted of downloading and storing all the documents available on the journals' websites, except for editorials and reviews. This procedure generated a total of: N = 1548 articles (Piñeiro-Naval and Morais, 2019). After their exhaustive examination, n = 120 publications were mentioned and referred to any of these fields: culture, heritage and/or tourism. A data that constituted 7.75% of the total.

2.1. ANALYSIS AND PROCEDURE VARIABLES

To undertake the objectives, an analysis procedure was designed inspired by similar empirical initiatives (Caffarel-Serra, Ortega-Mohedano and Gaitán-Moya, 2017; Goyanes, Rodríguez-Gómez and Rosique-Cedillo, 2018; López-Bonilla, Granados-Perea and López-Bonilla, 2018; Martínez-Nicolás, Saperas and Carrasco-Campos, 2019; Piñeiro-Naval and Mangana, 2018, 2019; Walter, Cody and Ball-Rokeach, 2018). The following variables were contemplated:

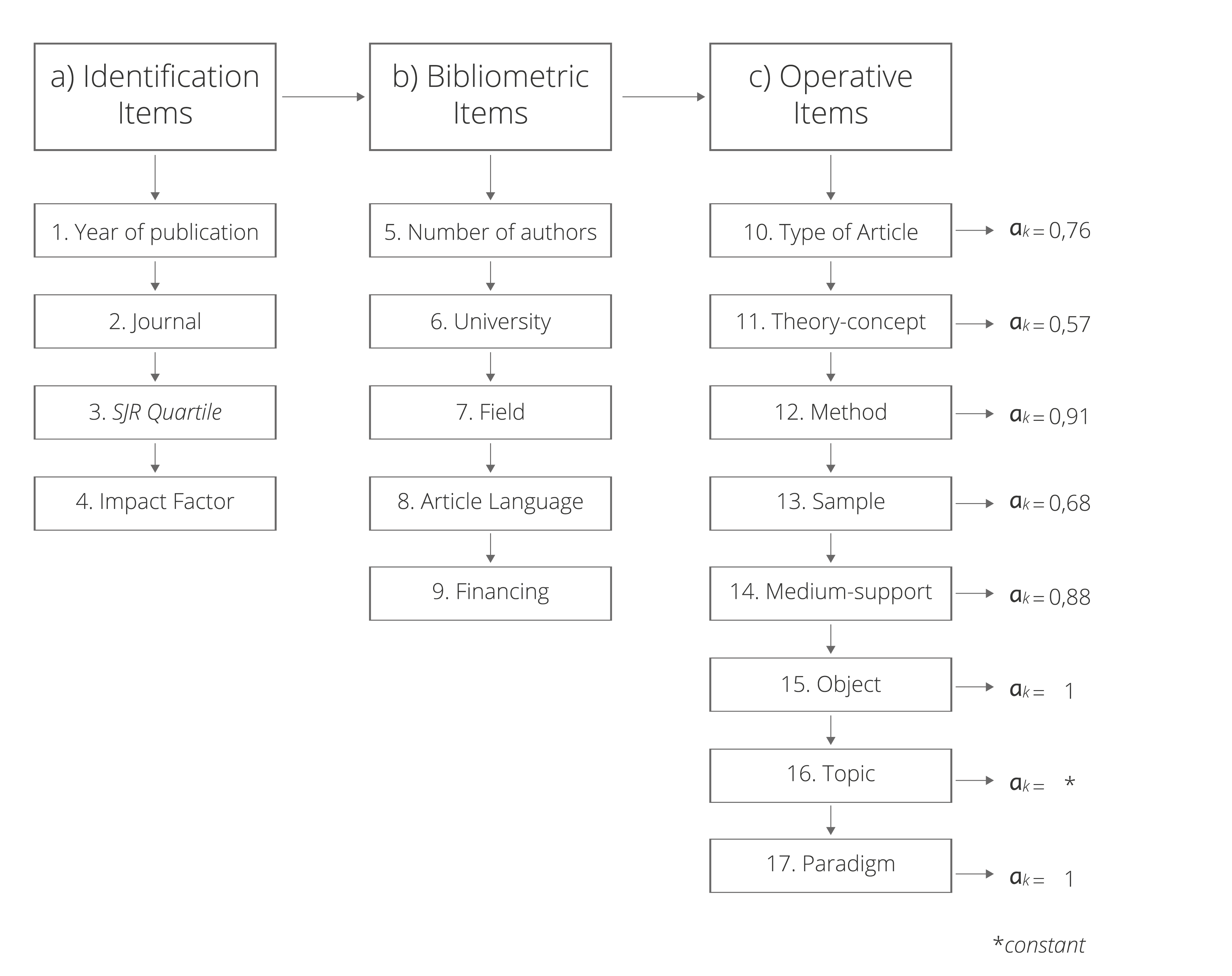

Figure 1. Scheme of the analysis items.

A total of 17 items were treated: 4 basic identification items, 5 bibliometric items and 8 analytical-operational items, whose response options will be detailed in the results section. Note that the values of items 3 and 4 were extracted as independent variables from the Scimago Journal & Country Rank repository, which facilitated their subsequent crossing with the data obtained here.

Finally, it should be clarified that a team of two analysts participated in the coding process, precisely the authors of this manuscript. After this process, a random subsample of 10% of the cases (n = 12) that both coders analyzed were selected to check the reliability of their work. The parameter used to calculate the reliability was the "Krippendorff's Alpha" (Krippendorff, 2004, 2011, 2017), found using the "macro Kalpha" (Hayes and Krippendorff, 2007) for SPSS, version 24. The average reliability of the 8 operating variables were satisfactory: M (αk) = 0.83 (SD = 0.16), see Figure 1.

3. RESULTS

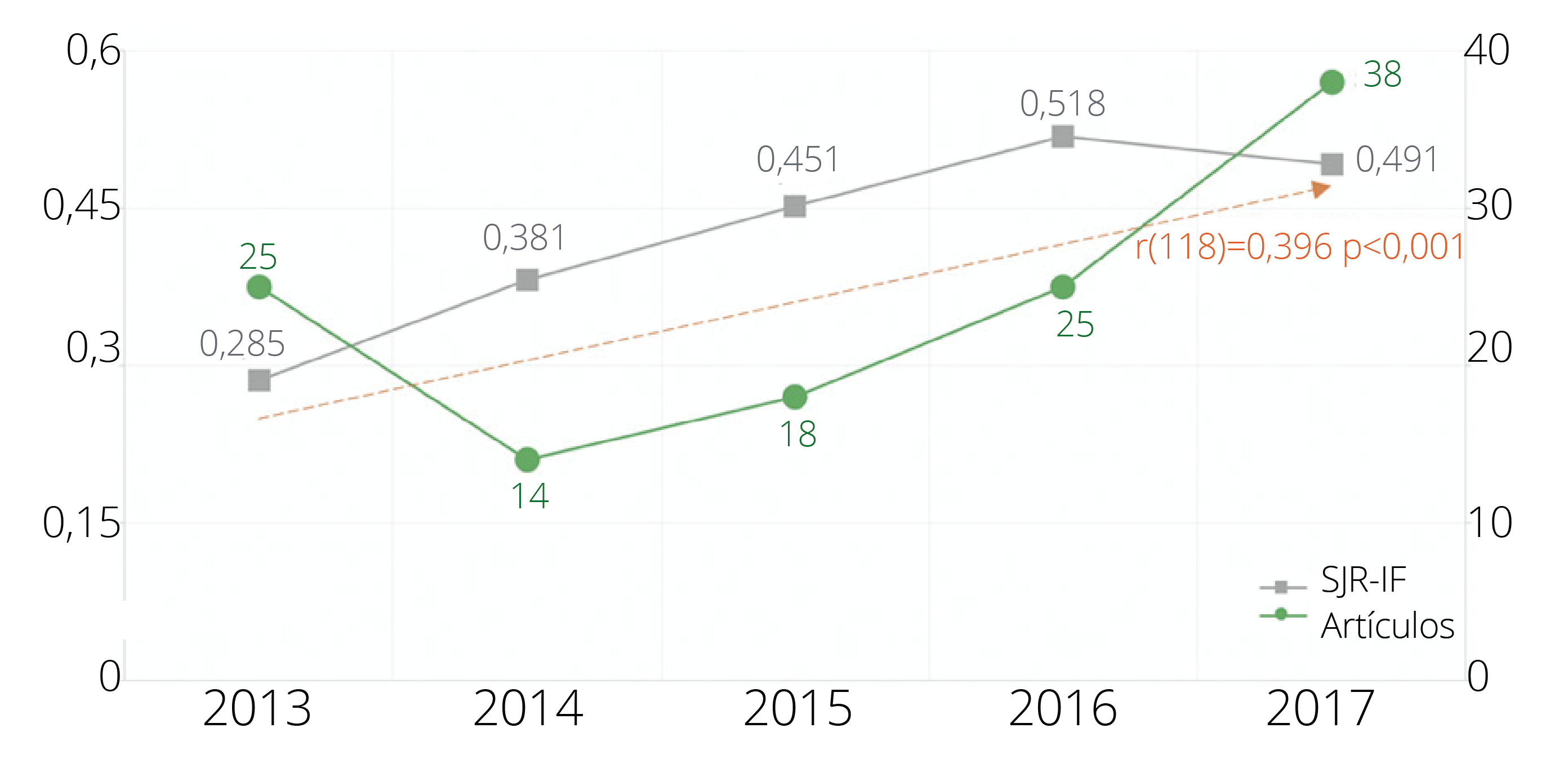

First, the timeline shown in Figure 2 reflects the annual evolution of both the average of published articles and their impact factor:

Figure 2. Timeline with the annual evaluation of the articles and their impact.

As of 2014, there is a constant increase in the number of manuscripts published annually, whose average amounts to: M articles = 24 (SD = 8.17); as well as its impact factor (M SJR-IF = 0.435, SD = 0.201). In 2017, there was a slight decrease compared to the previous year. Similarly, the correlation that occurs between both parameters is statistically significant [r (118) = 0.396, p <0.001], which shows that the more publications, the more impact academic production gets. It should also be said that this production is usually indexed in the first quartiles of the SJR ranking: 9.2% of the articles in the first quartile, 76.7% in the second, 7.5% in the third and 2.5% in the fourth. Finally, only 4.2% of the publications were not indexed in that year. The sample of 120 publications is distributed as follows according to the identified journals:

Figure 3. Number of documents according to the selected journals (frequencies).

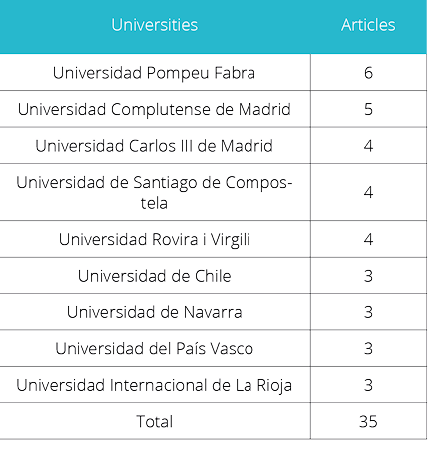

The most active headers in the dissemination of manuscripts related to culture, heritage and tourism in the Hispanic sphere are El Profesional de la Información from Spain and Palabra Clave at the Latin American level. As regards the universities of the authors, a total of 71 were identified, among which the following stand out:

Table 1. Most prolific universities.

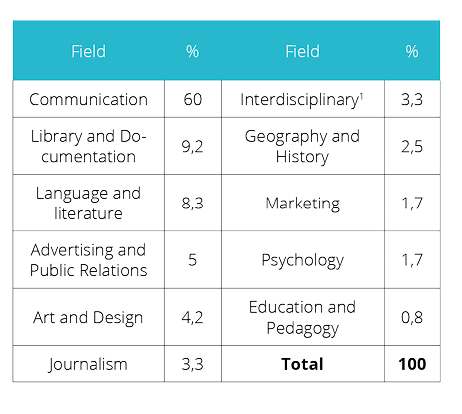

These 9 institutions, all of them Spanish except for one Chilean, represent only 12% of the total number of universities identified but account for 29% of the publications. If we continue to profile authorship, we find that their average amounts to: M authors = 1.8 (SD = 0.93). This data correlates with the impact factor [r (118) = 0.158, p = 0.085], although only tendentially. For this reason, it could not be asserted that a greater number of authors necessarily leads to a greater impact of the works. The field to which they usually subscribe is communication (60%), followed by library and documentation (9.2%) and language and literature (8.3%). However, a lot of interdisciplinarity is perceived, as can be seen in the following table:

Table 2. Disciplines to which the authors belong

The languages in which the articles are written have the following distribution: 41.7% in Spanish, 30% in Spanish and English and 25% in English only. These data show the clear will of editors and authors to internationalize the academic production, since 55% of publications in Hispanic impact journals are available in English. From the bibliometric point of view, the latest data has to do with the extra funding of the research, present in only 33.3% of the documents. On the other hand, there is a statistically significant correlation between having extra financing and the impact factor [r (118) = 0.203, p = 0.026], this will increase as researchers have more resources for projects.

At the analytical-operational level, the publications are usually empirical (75.8%) or theoretical-essayist (20%). Proposals that focus on the explanation of a methodology barely reach 4.2%. Table 3 includes both theories and concepts and the methods used:

3 The "interdisciplinary" category addresses cases in which there are several authors and all of them belong to fields clearly differentiated from each other.

Table 3. Theories, concepts and methods used (%).

As can be seen, the most used theories have to do with the construction of cinematographic narration (14.2%) and cultural studies (9.2%). Although it is striking that more than half of the manuscripts (51.6%) do not appeal to any kind of conceptual apparatus. On the other hand, the most recurrent methods are the case study (25.8%) and the discourse analysis (10%). If we divide them into qualitative (62.6%) and quantitative (37.4%), we immediately notice the prevalence of the first versus the second. The type of sample used in those empirical items (remember, 75.8% of the total) is commonly non-probabilistic (65.8%) versus probabilistic (10%). The main media are shown in figure 4:

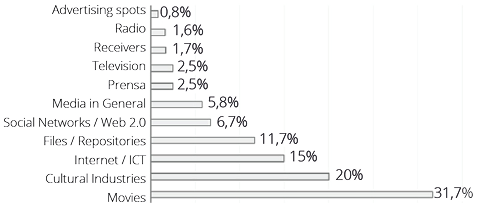

Figure 4. Media protagonists of the investigation (%)

Movies and series, as well as the rest of the cultural industries, are the most recurring media. Their total represented more than half of the documents (51.7%). The objects of study, in their broadest sense, serve the following percentage distribution:

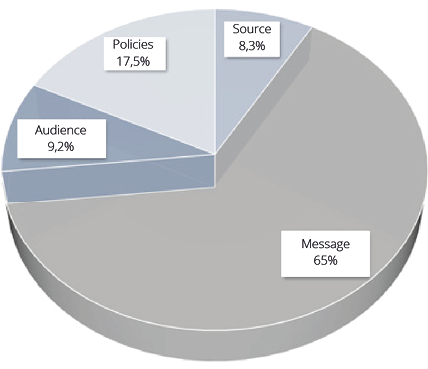

Figure 5. Study objects addressed in the publications (%)

The message (65%) is, without discussion, the protagonist of academic production versed in culture, heritage and tourism. It is followed very far by the policies (17.5%) of the communication linked to these areas. In what proportion each one of the subjects is attended? The following table shows the percentages related to these thematic domains, together with the epistemological paradigms to which the 120 publications observed adhere:

Table 4. General topics and epistemological paradigms (%)

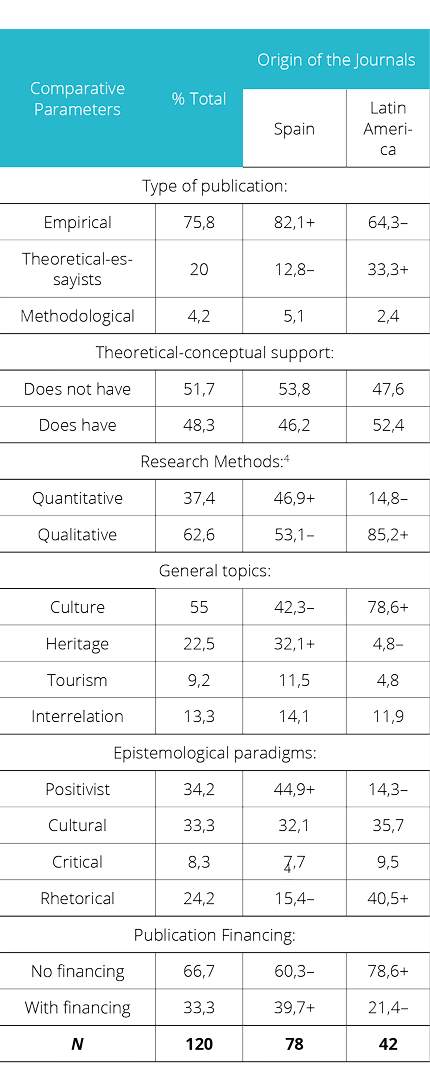

Culture is the subject that attracts the most attention from researchers (55%), while the positivist (34.2%) and cultural paradigm (33.3%) are practically tied. Finally, it is of great interest to outline the type of publications that are disseminated in both Spanish and Latin American journals:

Table 5. Comparison of headers based on their geographical origin (% per column).

Note: – Statistically lower value (analysis of corrected standardized residue) + Statistically higher value (analysis of corrected standardized residue)

Based on the data reflected in Table 5, Spanish journals are the ones that publish the most empirical works compared to Latin Americans, most represented by theoretical-essayist proposals [χ2 (2, N = 120) = 7.37, p = 0.025, v = 0.248]. From the point of view of the conceptual substrate, there are no statistically significant differences between the articles of some headers and others [χ2 (1, N = 120) = 0.424, p = 0.515, v = 0.059]. At a methodological level, there is a greater use of quantitative methods in publications from Spanish journals and qualitative methods in Latin American journals [χ2 (1, N = 120) = 8.34, p = 0.004, v = 0.303]. In turn, they usually contain a smaller proportion of studies with extra funding compared to their Spanish counterparts [χ2 (1, N = 120) = 4.12, p = 0.042, v = 0.185]. Regarding the topics, Spanish publications generate greater production around heritage, while Latin Americans focus more on cultural issues. [χ2 (3, N = 120) = 17.03, p < 0.001, v = 0.377]. Finally, the paradigms also show remarkable contrasts. Positivist paradigms prevail in Spanish journals and in rhetoric are more common on Latin American journals [χ2 (3, N = 120) = 14.80, p = 0.002, v = 0.351].

Finally, the average impact factor also indicates statistically significant differences [t (118) = 9.06, p < 0.001, d = 1.78], since the 4 headers of Spain (M SJR-IF = 0.53, SD = 0.16) surpass in this aspect the 3 Latin American (M SJR-IF = 0.26, SD = 0.13); and they do it through a "high" effect size (Cohen, 1988; Johnson et al., 2008).

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

To be more clearly interpretable, the main ideas that emerge from the data collected are described below.

At the bibliometric level, the total number of documents identified about culture, heritage and tourism amounted to 120, that is, around 8% of the total publications included in the magazines of the sample in the five years analyzed. This means a corpus that is not negligible if we stick to the multidisciplinary nature of scientific literature in communication, which causes a great thematic dispersion. The trajectory of this production is ascending, which confirms an increasing interest on the part of the academic community. This interest also translates into a high impact, although it is true that it experiences a slight setback in the last year analyzed: 2017. These considerations should be interpreted with caution because the present analysis is not longitudinal but transverse, so it would be necessary to observe a longer time period to indicate evolutionary trends more reliably. On the other hand, the universities to which the most prolific authors belong are located in Madrid and Barcelona, the two academic poles of reference at the national level. The co-authorship does not reach on average the two authors, although it is true that there is a very remarkable interdisciplinarity. According to Table 2, a dozen areas of belonging and a fairly high internationalization were identified through the use of English. There is also a lack of extra funding for these types of initiatives, an absolutely negligible aspect if we take into account the association between resources and impact: the more the first increases, the more the second will do.

From an analytical point of view, it is worth mentioning that there are many empirical works about cinema and other cultural industries, where the message is the object of the main study. The most recurrent theories have to do, precisely, with the construction and analysis of cinematographic narratives and the tradition of cultural studies. It is necessary to verify that no specific conceptual apparatus is used in more than half of the articles, which constitutes a weakness that should be corrected. The case study and discourse analysis prevail with regard to methods, that is, qualitative techniques. This causes that the samples also tend to lack probabilistic criteria for their design, since they conform more to a convenience model. Although the positivist paradigm is predominant, both cultural and rhetorical are very close to it. Likewise, culture as a general theme is reaffirmed in its position of primacy with respect to heritage and tourism. Recall that in this sense, it was already anticipated in the section of the state of the art that culture has always been closer to communicative research than the other two domains.

In addition to outlining a global portrait of scientific production, another objective was to establish comparisons. Spanish magazines, among which El Profesional de la Información stands out, publish more manuscripts on audiovisual heritage, museum archives and digital humanities. They are mostly empirical and positivist, where quantitative methods prevail. These investigations that exhibit a high impact index also tend to have extra funding with greater assiduity. Latin American magazines, among which Palabra Clave stands out, refer more to issues related to cultural industries and multicultural movements. They rely on the rhetorical or the qualitative empirical paradigm for the approach to publications of a theoretical-essayist profile. These documents have a lower impact index compared to their Spanish counterparts and a lower trend of additional financing.

Finally, it is necessary to insist on the inter and multidisciplinary nature of communication research. The variety of approaches and thematic richness are, without doubt, two strengths of this type of publications. However, it would be convenient for them to appeal to more robust theories or concepts. At the methodological level, it would be interesting to explore quantitative techniques, especially if we look at the particularities that digital society entails from the perspective of (hyper) abundance of data. These can be studied thanks to techniques such as automated content analysis or network analysis. It would also be important to analyze the capital role that users play in the current media world, whose peculiarities are observable thanks to surveys or experiments. This would cause the message and the receiver to share the protagonism in a more balanced way and, consequently, that diversity remains the predominant note in the field of communication, intimately related to culture, heritage and tourism. de la comunicación, íntimamente relacionado con la cultura, el patrimonio y el turismo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is part of a project funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (Ref. nº: SFRH/BPD/122402/2016) of Portugal.

REFERENCES

Bessière, J. (1998). Local development and heritage: traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas. Sociologia Ruralis, 38(1), 21-34. doi:10.1111/1467-9523.00061

Boyer, M., and Viallon, P. (1994). La communication touristique. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Caffarel-Serra, C., Ortega-Mohedano, F., and Gaitán-Moya, J. A. (2017). Investigación en Comunicación en la universidad española en el periodo 2007-2014. El Profesional de la Información, 26(2), 218-227. doi:10.3145/epi.2017.mar.08

Carvalho, P. (2018). Património, Turismo e Sociedade Digital: Teoria e Aplicação. In V. Piñeiro-Naval & P. Serra (Eds.), Cultura, Património e Turismo na Sociedade Digital: Uma perspetiva ibérica (pp. 21-48). Covilhã: Editora LabCom.IFP.

Castells, M. (2001). La Galaxia Internet. Barcelona: Areté.

Castells, M. (2006). Informacionalismo, redes y sociedad red: una propuesta teórica. In M. Castells (Ed.), La Sociedad Red: una visión global (pp. 27-75). Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

Calhoun, C. (2011). Communication as social science (and more). International Journal of Communication, 5, pp. 1479-1496.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd Ed.). Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Earlbaum.

Craig, R. T. (2008). Communication as a field and discipline. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication (pp. 675-688). Nueva York: Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecc074

de-la-Peza, M. C. (2013). Los estudios de comunicación: disciplina o indisciplina. Comunicación y Sociedad, 20, pp. 11-32.

Denzin, N. K. (2012). Triangulation 2.0. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(2), 80-88. doi:10.1177/1558689812437186

Denzin, N. K. (2015). Triangulation. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781405165518.wbeost050.pub2

Fernández-Quijada, D., and Masip, P. (2013). Tres décadas de investigación española en comunicación: hacia la mayoría de edad. Comunicar, 21(41), pp. 15-24. doi:10.3916/C41-2013-01

Goyanes, M., Rodríguez-Gómez, E. F., and Rosique-Cedillo, G. (2018). Investigación en comunicación en revistas científicas en España (2005-2015): De disquisiciones teóricas a investigación basada en evidencias. El Profesional de la Información, 27(6), 1281-1291. doi:10.3145/epi.2018.nov.11

Hanitzsch, T. (2007). Deconstructing Journalism Culture: Toward a Universal Theory. Communication Theory, 17(4), pp. 367-385. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00303.x

Hayes, A. F., and Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1(1), 77-89. doi:10.1080/19312450709336664

Johnson, B. T., Scott-Sheldon, L. A. J., Snyder, L. B., Noar, S. M., and Huedo-Medina, T. B. (2008). Contemporary approaches to meta-analysis in communication research. In A. F. Hayes, M. D. Slater, & L. B. Snyder (Eds.), The SAGE Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research (pp. 311-347). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Reliability in content analysis. Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Human Communication Research, 30(3), 411-433. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00738.x

Krippendorff, K. (2011). Agreement and information in the reliability of coding. Communication Methods and Measures, 5(2), 93-112. doi:10.1080/19312458.2011.568376

Krippendorff, K. (2017). Reliability. In J. Matthes, C.S. Davis y R.F. Potter (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0210

López-Bonilla, J. M., Granados-Perea, C., and López-Bonilla, L. M. (2018). Autores prolíficos líderes en la investigación turística española. Transinformação, 30(1), pp. 39-50. doi:10.1590/2318-08892018000100004

Marinho, S., and Vicente-Mariño, M. (2018). Uma paisagem da Epistemologia e Metodologia em Comunicação. Comunicação e Sociedade, 33, pp. 7-14. doi:10.17231/comsoc.33(2018).2903

Martínez-Nicolás, M., Saperas, E., and Carrasco-Campos, Á. (2019). La investigación sobre comunicación en España en los últimos 25 años (1990-2014). Objetos de estudio y métodos aplicados en los trabajos publicados en revistas españolas especializadas. Empiria, 42, 37-69. doi:10.5944/empiria.42.2019.23250

Marujo, N. (2012). Comunicação, Destinos Turísticos e Formação Superior. En S. Sebastião y R. Ribeiro (Eds.), Portugal: Destino a Comunicar. A Comunicação no Turismo Português (pp. 74-88). Lisboa: ISCSP-CAPP.

Marujo, N. (2015). O Estudo Académico do Turismo Cultural. TURyDES, Revista de Turismo e Desarrollo Local, 8(18), pp. 1-18.

Neuendorf, K. A. (2016). The content analysis guidebook (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Osorio, J. (2016). La aventura del turismo: resinificando la cultura a través del turismo y el patrimonio. International Journal of Scientific Management Tourism, 2(2), 285-295.

Pérez-Montoro, M. (2016). Gestión del conocimiento: orígenes y evolución. El Profesional de la Información, 25(4), 526-534. doi:10.3145/epi.2016.jul.02

Pfau, M. (2008). Epistemological and Disciplinary Intersections. Journal of Communication, 58(4), pp. 597-602. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00414.x

Piñeiro-Naval, V., Igartua, J. J., and Rodríguez-de-Dios, I. (2018). Implicaciones identitarias en la divulgación del patrimonio cultural a través de Internet: un estudio desde la Teoría del Framing. Communication & Society, 31(1), 1-21. doi:10.15581/003.31.1.1-21

Piñeiro-Naval, V., and Mangana, R. (2018). Teoría del encuadre: Panorámica conceptual y estado del arte en el contexto hispano. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 24(2), 1541-1557. doi:10.5209/ESMP.62233

Piñeiro-Naval, V., and Mangana, R. (2019). La presencia del framing en los artículos publicados en revistas hispanoamericanas de comunicación indexadas en Scopus. Palabra Clave, 22(1), e2216. doi:10.5294/pacla.2019.22.1.6

Piñeiro-Naval, V., and Morais, R. (2019). Estudio de la producción académica sobre comunicación en España e Hispanoamérica. Comunicar, 27(61), 113-123. doi:10.3916/C61-2019-10

Saperas, E., and Carrasco-Campos, Á. (2019). ¿Cómo investigamos la comunicación? La meta-investigación como método para el estudio de las prácticas de investigación en los artículos publicados en revistas científicas. In F. Sierra Caballero & J. Alberich Pascual (Eds.), Epistemología de la comunicación y cultura digital: retos emergentes (pp. 217-230). Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada.

Wallerstein, I. (2005). Las incertidumbres del saber. Barcelona: Gedisa Editorial.

Walter, N., Cody, M. J., y Ball-Rokeach, S. J. (2018). The Ebb and Flow of Communication Research: Seven Decades of Publication Trends and Research Priorities. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 424-440. doi:10.1093/joc/jqx015

Karen Julissa Barahona Posada

Baldwin Wallace University

Karen Barahona is an Assistant Professor of Spanish at Baldwin Wallace University. Her area of expertise is Latin American literature of the 20th-21st centuries with a focus on studies of testimony, gender, identity, memory and revolution in women’s fiction. Whether in the classroom or directing research projects, Karen's work is infused with her goal of promoting the experiences of unheard and non-dominant individuals and groups in Latin America. She is the recipient of the 2017-2018 Baldwin Wallace Excellence in Community Engagement Faculty Award and the 2019 Comunidad Oscar Arnulfo Romero Peace Mission Saint Romero Solidarity Award.

kbarahon@bw.edu

orcid.org/0000-0001-7955-5540

RECEIVED: January 11, 2020 / ACCEPTED: January 19, 2020

OBRA DIGITAL, 18, February - August 2020, pp. 47-56, e-ISSN 2014-5039

DOI: 10.25029/od.2020.252.18

Abstract

The revolutions of the 1970s and 1980s in Nicaragua and El Salvador put an end to the era of military dictatorships. Consequently, women redefined their political identity through revolutionary participation. Gioconda Belli reflected the Sandinismo in her works and marks the role of Nicaraguan women during the revolution in La mujer habitada (1998). In the same way, Claribel Alegría represented the Salvadoran revolutionary woman in her testimonial novel No me agarran viva (1983). The purpose of this work is to demonstrate how the literary works rewrite history to vindicate women as historical subjects in Nicaragua and El Salvador.

Keywords

Political identity, Subjectivity, Sandinista revolution.

Resumen

En Nicaragua y El Salvador las revoluciones de los años setenta y ochenta pusieron fin a la era de dictaduras militares, la mujer redefine su identidad política mediante la participación revolucionaria. Gioconda Belli reflejó el sandinismo en sus obras, y en La mujer habitada (1998) marca el papel de la nicaragüense durante la revolución. De la misma manera, Claribel Alegría representó la mujer revolucionaria salvadoreña en su novela testimonial No me agarran viva (1983). El propósito de este trabajo es demostrar como las obras reescriben la historia para reivindicar a la mujer como sujeto histórico en Nicaragua y El Salvador.

Palabras clave

Identidad política, Subjetividad, Revolución Sandinista.

Resumo

Na Nicarágua e El Salvador, as revoluções das décadas de 1970 e 1980 encerraram a era das ditaduras militares, as mulheres redefinem sua identidade política por meio da participação revolucionária. Gioconda Belli abordou o sandinismo em suas obras e, em La mujer habitada (1998), marca o papel da nicaraguense durante a revolução. Do mesmo modo, Claribel Alegría representou a mulher revolucionária salvadorenha em seu romance No me agarran viva (1983). O objetivo deste trabalho é demonstrar como as obras reescrevem a história para reivindicar as mulheres como sujeitos históricos na Nicarágua e El Salvador.

Palavras-chave

Identidade política, Subjetividade, Revolução Sandinista.

1. INTRODUCtioN

Given the Nicaraguan prominence in the revolutionary plight of the seventies, Gioconda Belli and Claribel Alegría dedicated themselves to writing about the Central American revolutionary movements. On one hand, Belli had participated with the FSLN (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional) in the overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship and her work had contributed to issues of love, sexuality, politics and revolution. On the other hand, the author Claribel Alegría (from El Salvador) had written about the revolutionary struggle of the FMNL (Frente Farabundo Martí de Liberación Nacional).

In the same way, Alegría's literary involvement in the process of seeking subjectivity of Central American women was determined by two sociopolitical factors: political discourses of revolutionary power and patriarchal society. Belli's militancy in the FMNL and Alegría's contributions form a literary trajectory that must be analyzed to fulfill its purpose of remembering the heroic work of men and women who gave their lives for the liberation of Nicaragua and El Salvador (Merril, 1993). This study provides insight into the process of seeking women's identity as a historical subject parallel to national liberation projects and contextualized in the two testimonial literary works: No me agarran viva (1983) y La mujer habitada (1998).

To explain the contribution of specific functions of testimonial discourses towards the construction of a national and individual identity, this research analyzes the testimonial functions of the denunciation of the categorization of women as “the other” of Linda Craft (1997), the representation of women in the novels of Laura Barbas-Rhoden (2003) and the reconstruction of the narrative by Margaret Randall (1994) in order to demonstrate how the literary works rewrite history to vindicate women as historical subjects for their revolutionary participation.

1.1. THE REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN AS A HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL SUBJECT